(Photograph by Frank Vincentz)

“I was to go out fishing tonight,” said the younger as he came in, “but I promised you to come, and you’re a civil man, so I wouldn’t take five pounds to break my word to you. And now”-taking up his glass of whisky-“here’s to your good health, and may you live till they make you a coffin out of a gooseberry bush, or till you die in childbed.” -J.M. Synge (The Aran Islands, 1907)

The Roots:

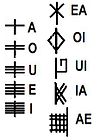

The fourth forfeda, and the twenty-fourth letter of the tree-Ogham, is Iphin the Gooseberry[i].

As discussed during the previous post, Liz and Colin Murray in the Celtic Tree Oracle do not ascribe the Gooseberry to Iphin. The double crossed lines are instead used for the Honeysuckle, while the Beech tree is given “the hook.” I am unsure of the reasons for this decision. These changes do not make sense to me, but I am well aware that Liz and Colin Murray were very deliberate in their choices. This differing of the order may simply be of interest, however, as many other Ogham systems follow their lead. This includes John Michael Greer as we have already stated.

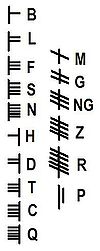

Robert Graves did not discuss the Gooseberry within the White Goddess and only spoke of the forfeda in the Crane Bag and Other Disputed Subjects. He called this forfeda “the Bones of Assal’s Swine”. The bones will be explored somewhat below as they do not effect the immediate discussion. Graves does put forward the possibility, though, that these bones were actually the discarded stems from the mushrooms that were eaten during ritual, the Aminita muscaria. In the Crane Bag and Other Disputed Subjects Graves says it is because “Assail was a lightening god and because mushrooms, called “little pigs” in Latin and Italian, were believed to be created by lightening and because hallucinogenic varieties of mushrooms were used in Greek and several Eastern religions for oracular purposes[ii].”

Nigel Pennick in Magical Alphabets does not add anything to the Gooseberry discussion either. He lists the 24th letter as the Guelder Rose or the Snowball tree. Pennick connects this plant to “the dance of life” and to the “mystic Crane Dance performed upon labyrinths throughout Europe, and to the crane-skin ‘medicine bag’ which ancient shamans used to hold their sacred power-objects.”

The Ogham tract does describe the tree as either the Pine or the Gooseberry[iii]. The Scots Pine, also called the Scots Fir at the time, has already been listed[iv]. For a separate meaning of this letter, instead of a duplication, we are then left to focus on the Gooseberry.

“Millsem feda, sweetest of wood, that is gooseberry with him, for a name for the tree called pin is millsem feda. Gooseberries are hence named. Hence it was put for the letter named pin, for hence pin, or ifin, io, was put for it.” – Word Ogham of Morann (the Ogham Tract[v])

“Amram blais, most wonderful of taste, pin or ifin, gooseberry. Hence for the letter that has taken its name from it, pin or iphin, io.” – Word Ogham of Mac Ind Oic (the Ogham Tract[vi])

Eryn Rowan Laurie in Ogam: Weaving Word Wisdom gives the Gooseberry, and the corresponding letter, the attributes of “Divine influences” and “sweetness of life”. Through this sweetness is found the association to Honey.

John Mathews in the Celtic Shaman interprets the word-Ogham “sweetest of wood” as representing “taste.” Caitlin Mathews in Celtic Wisdom Sticks uses this few to represent the direction of North. Robert Ellison in Ogham: the Secret Language of the Druids says that Iphin represents, “the Kindreds, especially of nature.”

It would seem that the Gooseberry is one of the most elusive “trees” found within the Ogham.

This plant is not often found in myth or folklore either, nor does it seem to have any direct ties to legends, beings or heroes. It is, however, used as a sympathetic magical remedy in at least two places that I am aware of.

“For a sty on the eyelid point a gooseberry thorn at it nine times, saying, ‘Away, away, away!’ and the sty will vanish presently and disappear.” -Lady Wilde (Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms & Superstitions of Ireland, 1887)

“In Suffock and other parts of these islands, a common remedy for warts is to secretly pierce a snail or ‘dodman with a gooseberry-bush thorn, rub the snail on the wart, and then bury it, so that, as it decays the wart may wither away.” – Edward Clodd (Tom Tit Tot: An Essay on Savage Philosophy in Folktale, 1898)

The Gooseberry is a close relative of the currant-berry and can be found, in its North American form, throughout the Pacific Northwest[vii].

Iphin, the Gooseberry, has sympathetic magical properties. It represents that which is tasteful and the divine influences which surrounds us in the sweetest of ways.

The Trunk:

“As for the other miscellaneous objects found in the Crane Bag: if one thinks poetically, not scientifically, their meaning leaps to the eye.” –Robert Graves (the Crane Bag and other Disputed Subjects)

As previously stated the forfeda, or the items found in the crane-bag by poets, are listed as ‘the King of Scotland’s Shears’(the X), ‘the king of Lochlainn’s helmet’ (with his face underneath, the four sided diamond), ‘the bones of Assail’s swine’ (the double lined X out to the side of the line), ‘Goibne’s smith-hook’ (the P or hook symbol), and Manannan’s own shirt’, which “is a map of the sea showing lines of longitude and latitude.”

We now turn our attention towards ‘the bones of Assail’s swine.’ Fortunately, this is the one character listed who is easily recalled from the stories of the Celts.

“Asal, Asail (genitive), Easal [cf. Irish asal, ass] A member of the Tuatha Dé Danann who owned a magical spear, the Gáe or Gaí Assail, and seven magical pigs. His spear was the first brought into Ireland. It never failed to kill when he who threw it uttered the word ‘ibar’, or to return to the thrower when he said ‘athibar’ [cf. Irish ibar, yew tree, yew wood]. T. F. O’Rahilly observed that the Gáe Assail was a lightning spear, like the weapon of Thor, which also returned to the hand that hurled it. When Gáe Assail had been taken to Persia, Lug Lámfhota obliged the sons of Tuireann, Brian, Iuchair, and Iucharba, to retrieve it for him. Another task of those same children of Tuireann was to retrieve the seven magical pigs of Assal ‘of the Golden Pillars’, who could be killed and eaten and would be alive and ready to be slaughtered again the next morning. The bones of the pigs of Assal are in the crane bag of Manannán mac Lir. See OIDHEADH CHLAINNE TUIREANN [The Tragic Story of the Children of Tuireann].” – James MacKillop (Oxford Dictionary of Celtic Mythology)

The recovery of these pigs by the children of Tuireann is one of the tasks that was given to them by Lugh for murdering his father. It is this series of quests which kills them in the end, even after they had accomplished all of them.

“’And do you know what are the seven pigs I asked of you? They are the pigs of Easal, King of the Golden Pillars; and though they are killed every night, they are found alive the next day, and there will be no disease or no sickness on any person that will eat a share of them.’” – Lady Gregory (Gods and Fighting Men, 1904)

These pigs would not only provide a never ending source of sustenance for their owners, but they were preventers of illness as well.

(Amanita muscaria. Photograph by Onderwijsgek)

It becomes important to remember that these items, including the bones, would disappear from the crane-bag when the tide was ebbing and reappear when the tide was full.

The mystery then becomes apparent. Why would the bones only be present in the bag and never the animal whose flesh was to be enjoyed? Would these pigs, then, be considered whole when they are missing from the bag? Does this mean that the pigs would have to be eaten before a certain time of the day such as the high tide? Could this tide actually represent a moon cycle, or a time of day, instead of the literal tide?

Perhaps, it is the bag of Manannan that returns the flesh to their bones before these pigs rise from the dead again? Maybe, instead, these tales are suggesting that the eating of the flesh is a part of the ritual that takes place at high tide, or as high tide approaches?

Obviously these are questions of interest, meditation, and contemplation only. To me, they are incredibly fascinating ones to consider, though.

The Foliage:

The following portion of this blog was here from Oct 20, 2011. I decided to leave it…

As we approach the final Ogham letter, Mor or “the Twin of Hazel”, I have been struggling to meet the deadlines I have put upon myself as far as posting these. Although this is not a heavily trafficked blog, I use this area to increase my awareness of the Ogham and to share any possible insights with fellow seekers. It’s very important to me that I maintain a sense of discipline, especially as it pertains to my spiritual practice, regardless of if I had one reader or hundreds.

I plan to continue through the next cycle of the half year, starting again with Birch, by sharing those pieces of information that I had left out the first time through – as well as recent discoveries – and will then share some of the other great Ogham minds such as Caitlin and John Mathews or Robert Lee Ellison. At some point, it would be nice to get some quotes from Charles Graves on here as well.

I do feel compelled to share, however, that I have been meeting with greater difficulties in publishing these posts and I apologize if they are not as polished as they could have been.

I have been undergoing aggressive chemotherapy treatments for a form a testicular cancer that has spread post surgery. I’ve been dealing with this for some time (the surgery was a year earlier) but only over the last month have I been getting these treatments. The outlook is very positive and a full recovery is expected. In the meantime, however, it is not the most fun I have ever had.

I will do my best to continue to post these for as long as I can. My intention is that there will be no interruption. I am usually pretty good at that one, the intention part anyways. 🙂

As of April 11, 2012, I am doing much better. I still have bad hair – or way less of it – and tire pretty easy. The chemo cycles are finished but it will be two years before they deem that I am cancer free.

“What shocked them the most was his [France’s] suggestion that the awareness of plants might originate in a super-material world of cosmic beings to which, long before the birth of Christ, the Hindu sages referred as ‘devas’ and which, as fairies, elves, gnomes, sylphs and a host of other creatures, were a matter of direct vision and experience to clairvoyants among the Celts and other sensitives. The idea was considered by vegetal scientists to be as charmingly jejune as it was hopelessly romantic.” – Peter Tompkins and Christopher Bird discussing Raul France (the Secret Life of Plants, 1973)

[i] The Ogham is not just a tree alphabet. See previous posts.

[ii] Quoting Early Irish Myth and History by Rahilly.

[iii] http://www.maryjones.us/ctexts/ogham.html

[iv] The Silver Fir is not the correct tree for Ailm. The Silver Fir did not exist in Ireland at the time of these writings and was introduced much later. The texts of the time, and sometimes sources later even to this day, referred to the “Scots Pine” as the “Scotch Fir.” The terms were used interchangeably Robert Graves ascribed the Silver Fir to Ailm, not likely being aware of this fact.

[v] http://www.maryjones.us/ctexts/ogham.html

[vi] Ibid.