“Since early times holly has been regarded as a plant of good omen, for its evergreen qualities make it appear invulnerable to the passage of time as the seasons change. It therefore symbolizes the tenacity of life even when surrounded by death, which it keeps at bay with strong protective powers.” Jacqueline Memory Paterson (Tree Wisdom: the Definitive Guidebook)

The Roots:

As discussed previously, Holly is a tree often associated with warriors, battle and death.

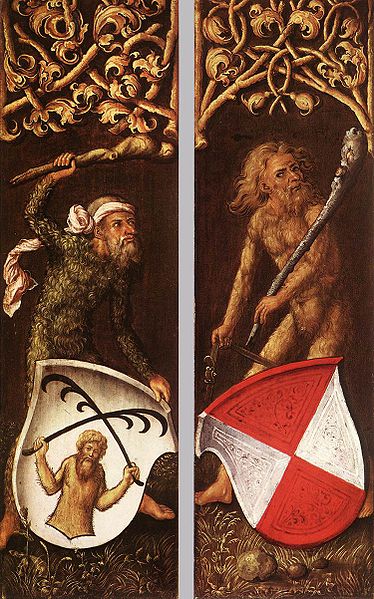

Holly is a leaf bearing evergreen tree, which has come to represent both the Wildman and the darkening of the year as the Holly King[i]. Perhaps both of these images are related to one another? The wild beast that exists within us is also repressed or destroyed at the height of that darkness within us – just like the Holly King so that we are not consumed and swallowed by our own animalistic nature. Just like the Holly King is killed by the Oak King on the darkest night of the year, the Wildman, who hugs the shadows, is repressed – or temporarily killed – during our own darkest hour.

John Mathews in the Celtic Shaman leaves is with a clue regarding the Holly as being “a third of…” something that remains unstated. Previous writers have explained this third portion that is mentioned to represent either chariot wheels (Holly axle,) or the third part of a weapon (maybe a spear shaft?).

Robert Ellison in Ogham: the Secret Language of the Druids says that Holly represents “justice and balance.” He also mentions the wheel and the weapon when he quotes previous Word-Oghams within his book.

Caitlin Mathews’ divination system found within Celtic Wisdom Sticks equates Holly with a type of cyclical wisdom. Her interpretations for Holly are all related to previous experiences holding answers for us in the present. As history repeats itself, the individual should know what actions are needed either logically or intuitively. In this way, Holly is always guiding us forward.

Holly represents half of the year from the summer solstice to the winter solstice. Holly, then, may also represent all that is dark or unkind such as our animalistic natures, battle and death. Any cycle can be seen as being symbolic of the cycle of life and death. By keeping this knowledge in perspective we simplify life and become wiser.

The Trunk:

Holly has an unusual role within Celtic mythology. It is a role which is not often discussed and may be overlooked. Holly often seems to be the mediator between the world of humans and that of the beasts.

Jacqueline Paterson quotes Pliny when she says that “if Holly wood was thrown in any direction it will compel the animal to obey.” While the reference to Pliny may not be as reliable as some of the Celtic sources, it deserves to be mentioned as support for the argument that Holly had special powers over beasts.

In the Mabinogion[ii] we bear witness to some unexplained magic. Taliesin helps Elphin (who saved him from the salmon weir) win a horse race with the use of Holly. We are not told exactly what the Holly does, but it seems to be instrumental in helping Elphin win the race.

“Then he (Taliesin) bade Elphin wager the king, that he had a horse both better and swifter than the king’s horses. And this Elphin did, and the day, and the time, and the place were fixed, and the place was that which at this day is called Morva Rhiannedd: and thither the king went with all his people, and four-and-twenty of the swiftest horses he possessed. And after a long process the course was marked, and the horses were placed for running.

“Then came Taliesin with four-and-twenty twigs of holly, which he had burnt black, and he caused the youth who was to ride his master’s horse to place them in his belt, and he gave him orders to let all the king’s horses get before him, and as he should overtake one horse after the other, to take one of the twigs and strike the horse with it over the crupper, and then let that twig fall; and after that to take another twig, and do in like manner to every one of the horses, as he should overtake them, enjoining the horseman strictly to watch when his own horse should stumble…”

The youth is also instructed to throw down his cap when his own horse (actually Elphin’s) stumbles. They dig where the cap has fallen and cauldron of gold is found. Taliesin then hands the treasure over to the “unlucky” Elphin as a reward for saving him.

In Gods and Fighting Men by Lady Gregory we find more Holly references. We are given a poem attributed to Finn (like Taliesin he was possessed with all knowledge). The poem seems more like a riddle for the initiated than a simple reflection. Its true meanings may elude us. The mention of Holly is interesting though.

“There is a hot desire on you for the racing horses; twisted Holly makes a leash for the hound.”

While this reference could have many other possible explanations or interpretations, we should remember that good Celtic poetry was often rife with double meanings. The songs of these enlightened bards were meant to be studied and contemplated. This reference to Holly could easily be a statement of its perceived powers.

Within the same text we find that Diarmuid and Grania are on the run from Finn. For a short while they are accompanied by a servant named Muadhan who seems to be a beast man of some sort.

Muadhan enters the story suddenly and leaves suddenly. He carries Diarmuid and Grania on his back over rivers and when they are too tired to walk. He pulls a “whelp” from his pocket and throws it at one of Finn’s hounds killing the canine enemy. Every night he also catches salmon for all three of them. Muadhan lives very closely to the land and his methods are very interesting.

“And he went himself into the scrub that was near, and took a straight long rod of a quicken-tree, and he put a hair and a hook on the rod, and a holly berry on the hook, and he went up the stream, and he took a salmon with the first cast. Then he put on a second berry and killed another fish, and he put on a third berry and killed the third fish. Then he put the hook and the hair under his belt, and struck the rod into the earth, and he brought the three salmon where Diarmuid and Grania were, and put them on spits.”

Here we see that Muadhan seems to live more closely to the land and be somewhat of a beast himself. He also seems to be carnivorous. Interestingly, Muadhan always keeps the smallest portion for himself.

(Wild men support coat of arms in the side panels of a 1499 portrait by Albrecht Durer[iii])

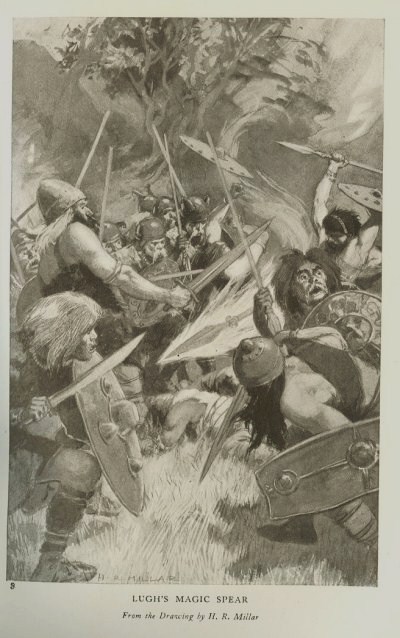

The story of Cuchulain – whose name means “the hound” – also has some interesting Holly references. Joseph Dunn’s translation of the Tain Bo Cuailnge is the source of this quote:

“On the morrow Nathcrantail went forth from the camp and he came to attack Cuchulain. He did not deign to bring along arms but thrice nine spits of holly after being sharpened, burnt and hardened-in fire.”

Nathcrantail casts all of these “darts” but does not kill Cuchulain. He does, however, manage to interrupt his bird hunting and scatters his prey.

“It was then, when Nathcrantail threw the ninth dart that the flock of birds which Cuchulain pursued on the plain flew away from Cuchulain. Cuchulain chased them even as any bird * of the air.* He hopped on the points of the darts like a bird from each dart to the next, pursuing the birds that they might not escape him but that they might leave behind a portion of food for the night. For this is what sustained and served Cuchulain, fish and fowl and game on the Cualnge Cow-spoil.”

We see then that Cuchulain is more of a beast than a man due to his ability to leap through the air and his need to capture his own meals. Cuchulain also seems to be carnivorous.

When Cuchulain is asked why he did not kill Nathcrantail he says it is because his enemy was unarmed. Clearly the Holly “darts” are not viewed as weapons by Cuchulain in the conventional sense.

“Dost not know, thou and Fergus and the nobles of Ulster, that I slay no charioteers nor heralds nor unarmed people? And he bore no arms but a spit of wood.”

Also found in the book, it is a “spit of holly” that finally wounds Cuchulain. The wound is self inflicted during a bout of rage. There is a suggestion, then, that Holly may be a sort of Kryptonite to Cuchulain. Where his enemies could not succeed with swords and spears, he accidently accomplishes with a sharpened piece of burnt wood.

Paterson speaks at length of the Holly King and the Wildman within Tree Wisdom. She explains in which ways she sees them as being one and the same.

“Thus we see that the Wildman expressed the procreative essence of Nature, the Godhead. And from his primal beginnings and through translations of his manifold energy he came to personify specific aspects of the energies of Nature, from which forms like the holly and oak kings evolved, embodiments par excellence of the seasonal forces associated with the dark and light periods of the year.”

It is not beyond the realm of possibility that Holly had a more specific use to the Celts of old. It seems to be the gate keeper and the guardian of the wild aspect of nature as well as the ruler over all of those that are wild.

In both Ireland and Wales, the wood of Holly is burnt before it is used[iv].

The Foliage:

The following information is from Cat Yronwode’s Herb Magic[v] website. The wording is very detached to protect them from possible lawsuits. It may also be possible that Holly is not a common herb used in Hoodoo. These uses for Holly seem to be mostly protective.

Holly can be burned with incense to protect the home and to bring good luck. Holly can also be placed above the door for protection and to invite into the home benevolent spirits.

As these are all qualities that we wish to attract to the home, Holly would best be used during the waxing phase of the moon.

“The Holly is best in the fight. He battles and defends himself, defeating enemies, those who wish to destroy him, with his spines. The leaves are soft in summer but in winter, when other greenery is scarce and when the evergreen Holly is likely to be attacked by browsing animals, the leaves harden, the spines appear and he is safe.” – Liz and Colin Murray (The Celtic Tree Oracle)

[i] Jacqueline Memory Paterson. Tree Wisdom: the Definitive Guidebook.

[ii] Lady Charlotte Guest translation.

[iv] As related in the tales involving Finn and Taliesin.