(Bluebells in Portglenone Forest in spring. David Iliff[i])

“Nemeton. A Gaulish word apparently meaning ‘sacred grove’ or ‘sanctuary’ appears whole or in part in several place names. Nemetona, Nemontana [goddess of the sacred grove; see NEMETON] Gaulish and British goddess whose name appears in many ancient inscriptions.” – James MacKillop (Dictionary of Celtic Mythology)

The Roots:

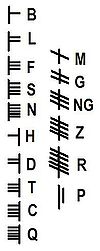

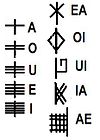

The twenty first letter of the Ogham, and the first letter of the forfeda, is Koad, the Grove.

Koad can also be Ebad, representing the Aspen or Woodbine instead. Reconstructionists usually do not refer to this letter as “the Grove.”

As discussed during the last entry, the Grove seems to have been an introduction by Colin and Liz Murray in an attempt to solve the riddle of the crane-bag presented by Robert Graves in the Crane Bag and other disputed subjects. This choice may have also served a duel purpose, however, as the Aspen tree had already been listed within the Ogham in its tree form.

Whatever their intention, Grove as a separate meaning, and letter, for magical users of the Ogham has seemed to hold fast since its initial introduction.

According to Liz and Colin Murray in the Celtic Tree Oracle, the Grove is linked to all “sacred places, traditionally near springs.” It is described as the “all knowledge” or the gathering together of that which one already knows.

Nigel Pennick in Magical Alphabets adds that the Grove represents the unity of all 8 festivals[ii]. He also says that “the Grove represents the colours of the forty shades of green.” The Grove is the point of total clarity.

Eryn Rowan Laurie in Ogam: Weaving Word Wisdom calls the Ogham letter Ebad and equates it not with a tree, but with the Salmon. She says that the meanings of the letter are, “carrier of wisdom, vehicle of inspiration and spiritual nourishment.” The association to salmon and to the Aspen is common amongst reconstructionists in regards to this few. The few is described in the Tract as being “the best swimming letter.” Aspen is buoyant and the Salmon is mentioned again later in the document[iii].

John Michael Greer, like the Murrays, also associates Koad to the Grove. He says of the letter that it is, “a few of central balance and infinite possibility, symbolized by a grove of many trees; the presence of many factors, the possibility of freedom.[iv]”

Robert Graves lists Koad as “the King of Scotland’s Shears” in the Crane Bag and other disputed subjects. He does not list any of these extra letters, the forfeda, as having any part whatsoever to do with the tree calendar theory that he had first presented in the White Goddess. It was during this philosophical shift between Graves and the Murrays that various interpretations of the Ogham outside of academic areas became mainstream.

In the Celtic Shaman by John Mathews, the work kenning “most buoyant of wood” is interpreted as representing “ability.” Caitlin Mathews in Celtic Wisdom Sticks does not use the forfeda in the same way, but uses this letter to represent the direction of South.

Robert Ellison in Ogham: the Secret Language of the Druids, uses White Poplar for the letter Ebad. He says that this letter represents, “buoyancy and floating above problems.”

As the Grove, Koad can be linked to all of the other trees and to any of the stories found within the forests of Celtic myth. The Grove can also represent a meeting point of intention, a magical encounter, or even a holy place.

The Trunk:

“As for the other miscellaneous objects found in the Crane Bag: if one thinks poetically, not scientifically, their meaning leaps to the eye.” Robert Graves (the Crane Bag and other Disputed Subjects)

As previously stated the forfeda[v], or the items found in the crane bag by poets, are listed as ‘the King of Scotland’s Shears’(the X), ‘the King of Lochlainn’s helmet’ (with his face underneath, the four sided diamond), ‘the bones of Assail’s swine’ (the double lined X out to the side of the line), ‘Goibne’s smith-hook’ (the P or hook symbol), and Manannan’s own shirt’, which “is a map of the sea showing lines of longitude and latitude.[vi]”

Thus the forfeda becomes a riddle of magical and mythological contemplation.

So who is the king of Scotland and why are his shears important? Why does Manannan possess these items in the first place? Has he vanquished the owners of these objects in battle, or does he hold the items for safekeeping? Could these artifacts be being saved for ritualistic purposes, having been set aside for their owners within the sanctity of the crane bag? Or can they, the items, be being held hostage themselves?

There may not be a good answer to any of these questions. One can only study and contemplate as to what these items may have meant to the Celts of old. The old texts leave us with riddles that may or may not really mean anything.

Interestingly enough, though, the most famous story of shears found in Celtic mythology may also have ties to Scotland as well.

Twrch Trwyth was a king who had been transferred into a mighty boar because of his previous sins. In Jeffery Gantz’s version of the Mabinogion , Arthur himself says that “he was once a king but because of his sins god turned him into a pig.”

In the tale How Culhwch won Olwen, found in the Mabinogion, the story is revealed in its entirety- at least the portions that have survived down into our present era.

Culwch is described as the son of the ruler of Kelyddon in the Gantz version, but in others he is seen as the son of Prince Kelyddon. Could Kelyddon, the place, be Caledonia or Scotland? It may be a stretch, but the frequent mention of other countries in the old tales shows a great deal of contact between the Celtic ancestors including even the transfer of these stories and legends.

Culwch is the ultimate owner of the shears by the end of the story, but it is Caw of Scotland who uses the tool. Could Caw have been a prince or a king? In other versions of the story he is Kaw of North Britain. It may even be suggested that he is one of Culwch’s own men by his lack of mention in comparison to all of the other heroes found in the story.

Regardless, Culwch falls in love with the maiden Olwen who is the daughter of the giant Ysbaddaden. Culwch seeks out the giant with the help of Arthur and his men. Culwch is revealed to be the first cousin of Arthur, who gives him a haircut at the beginning of the tale[vii]. Culwch recruits Arthur and his men and they set off to find Ysbaddaden. When the giant is found, Culwch asks for the price of his daughter. Ysbaddaden then gives to Olwen a long series of impossible tasks that he must accomplish in order to win her hand. These trials need to be completed in order to win the giant’s daughter and in order to “cut off his head.”

(Clan Carter-Campbell family crest badge. Craigenputtock[viii])

The greatest task of all of them, and the only one told in detail, is the hunting of Twrch Trwyth. The great boar holds between his ears the comb and shears[ix] (and a razor) needed to give Ysbaddaden his final hair cut before the giant is executed.

To accomplish this task an army of men, led by Arthur, must first find the Mabon[x] whose help they need to get the boar’s treasures. Only he, with the magical devices, can handle the hound needed to catch Twrch Trwyth. To find the Mabon, however, they must first locate the oldest animal in the world who should know of the Mabon’s whereabouts. The heroes interview several of the oldest of animals, eventually talking to the oldest of them all, the salmon. The Salmon of Llyn Llyw then carries some of Arthur’s men up a stream, on his shoulders, to a prisoner’s quarters where the Mabon is being held. A battle then helps them to release the Mabon from captivity.

Eventually the party is ready to go after the boar himself having procured the proper hunting dogs, magic leash, collar, chains and men with extraordinary abilities.

When the men first turn their attention on Twrch Trwyth he has already destroyed “a third” of Ireland. When they later return to engage him more directly, he has destroyed “a fifth” of Ireland. The local Irish then help the men of Arthur fight the great boar and his seven sons. Many are slain. The Boar and his offspring flee Ireland and go to Wales where they began to kill the people and attack the countryside. In a battle for each of the shaving treasures many men are lost. Eventually, however, Twrch Trwyth is dead along with all of his sons.

The time finally comes for Ysbaddaden’s haircut. As mentioned, though, in the story this is done by Caw of Scotland and not by Culwch at all.

“Caw of Scotland came to shave the giant’s beard, flesh and skin right to the bone and both ears completely. ‘Have you been shaved?’ Asked Culhwch. ‘I have,’ said Ysbaddaden. ‘Is your daughter mine now?’ ‘She is. And you need not thank me, rather Arthur, who won her for you; of my own will you would have never got her. Now it is time for you to kill me.’ Goreu son of Custenhin seized Ysbaddaden by the hair and dragged him along to the dunghill, where he cut off his head and set it on a stake on the wall. They seized the fortress and the land, and that night Culhwch slept with Olwen, and as long as he lived she was his only wife. Then Arthur’s men dispersed to their own lands.” –Jeffery Gantz translation.

In the Crane bag and other Disputed Subjects Robert Graves explains how the shirt of Manannan is really the latitude and longitude lines of a sea map. In this light Colin and Liz Murray took a closer look at the King of Scotland’s Shears.

First of all what does the letter look like? An X on a map if we’re still thinking along those lines. Perhaps we’re looking at another map key; that of a significant destination? An X certainly meant treasure by the time of the Ogham Tract or the recording of Celtic legends.

In a Celtic forest there can be only one place of treasure, and that would have been the place of the nemeton or Grove. The idea that the shears could actually create such a place, by the hands of Manannan or some other god, seems to give the idea further credence. The Grove is a holy place usually not created by the hand of man. It exists in the forest but in a sense it is separate. It unifies everything and yet seems somehow apart or above. It is where the Salmon of wisdom feasts on the nuts of the hazel.

There may be deeper mysteries here, however. This line of thinking seems to have been the path that was taken by Liz and Colin Murray as they sought the answers to the final riddles of the forfeda. If this is true, then why didn’t they also solve the riddle for the other three letters left? Manannan’s shirt was the Sea and the King of Scotland’s Shears was the Grove. What about Oir, Uilleand and Phagos?

Other questions still need to be answered as well. What can these symbols really mean? Who are these men and why does Manannan hold these items within the crane bag at all?

There is much to be pondered.

The Foliage:

For some time I have been meaning to acknowledge the Trees For Life: Restoring the Caledonian Forest website and organization properly for the enormity of the work that they do. Their website describes this work below as follows:

“Trees for Life is the only organisation specifically dedicated to restoring the Caledonian Forest to a target area of 600 sq miles in the Scottish Highlands. We work in partnership with the Forestry Commission, RSPB and private landowners, and own and manage the 10,000 acre Dundreggan Estate.

“Each year we run over 45 Conservation Holidays. Hundreds of volunteers join us annually in planting over 100,000 trees in protected areas, and carry out other restoration work such as seed collection and propagation of young trees and rare woodland plants. We have planted over 923,000 trees since 1989.”

I have enjoyed and sourced Paul Kendall’s articles on mythology within livinglibraryblog several times[xi]. Kendall’s writing brings a certain magic to the reality of the project that the Trees for Life organization has undertaken. The website is a beautiful resource of knowledge and a testament to the times of our ancestors… and even before. The goal to reforest portions of the highlands, seemingly unachievable, has been taking place one step at a time.

The organization offers several ways to donate or help out. A person can plant a tree or even just become a member for a small fee. What is most interesting to me, however, is the option of planting a Grove.

A person can make a donation by planting a Grove in someone’s memory, or for an important landmark like a wedding or a birth. It’s an excellent way to honour someone or some event while still being able to give back something long-lasting and meaningful. It is a way in which to reconnect with the past and to offer healing to an old friend.

To check out the sight, or to consider making a donation, please visit:

http://www.treesforlife.org.uk

“In view of the fact that don Juan was acquainting me with a live world, the processes of change in such a live world never cease. Conclusions, therefore, are only mnemonic devices, or operational structures, which serve the function of springboards into new horizons of cognition.” – Carlos Castaneda (the Teaching of Don Juan: a Yaqui Way of Knowledge)

[ii] The eight turning times of the year that neopagans tend to recognize in ritual and respect.

[iii] http://www.maryjones.us/ctexts/ogham.html

[iv] The Druid Magic Handbook.

[v] See blog post: An Introduction to the Forfeda.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Thus the story begins and ends with the same ritualistic act.

[ix] Sometimes scissors.

[x] The Mabon is often described as a mysterious Celtic Christ.

One thought on “Koad (Salmon or the Grove)”