“On the summit of his ancient stronghold, South Barrule Mountain, the god Manannan yet dwells invisible to mortal eyes, and whenever on a warm day he throws off his magic mist-blanket with which he is wont to cover the whole island, the golden gorse or purple heather blossoms become musical with the hum of bees, and sway gently on breezes made balmy by the tropical warmth of an ocean stream flowing from the far distant Mexican shores of a New World.” – W. Y. Evans-Wentz (Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries)

1) The Roots: Background information

2) The Trunk: Celtic Mythology and Significance

3) The Foliage: Spells using the Plant

The Roots:

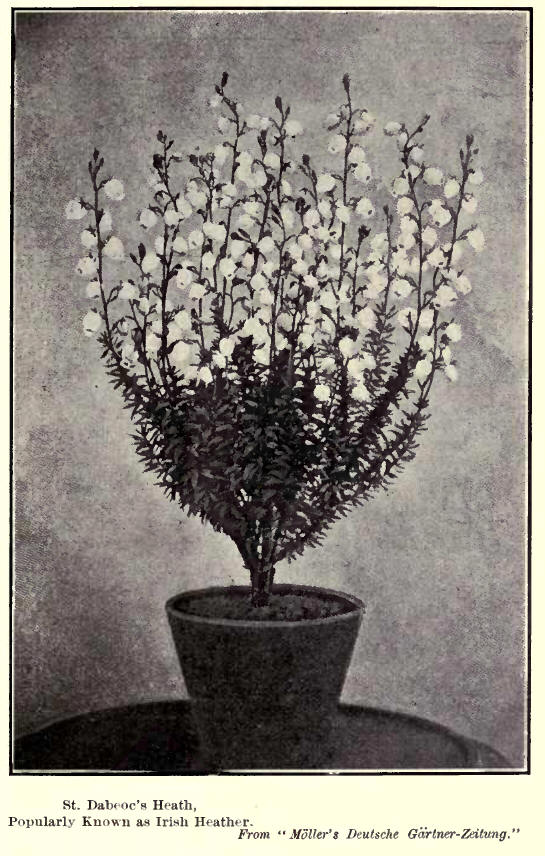

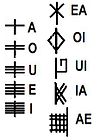

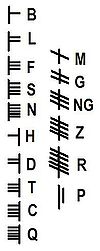

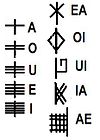

Ur is the eighteenth letter of the Ogham. The tree that is usually associated with this letter is the Heather[i].

The Ogham Tract’s kenning[ii] “in cold dwelling” is given the meaning of “fear” in John Mathew’s book the Celtic Shaman.

Robert Ellison in Ogham: Secret Language of the Druids says that the Heather is associated with “healing and homelands.” He also says that the herb is connected with the Celtic fairies and thus has magical uses.

Eryn Rowan Laurie in Ogam: Weaving Word Wisdom states that the Ogham letter Ur is representative of death, fate and finality through its connection to the soil[iii]. Laurie also claims that Heather –independent from the letter- is linked to poverty.

Catlin Mathews in her book Celtic Wisdom Sticks says that Ur’s word-Ogham kennings all refer to either the earth or “growth cycles.” Her divination system supports these reflections as the interpretations refer to hard work, growth, and following one’s life path.

The Trunk:

“Heather is the four leaf clover of the Scottish Highlands.[iv]” In fact, it is often even seen as a Scottish national symbol. As a result Heather is found on many of the Scottish clan badges.

The importance of Heather to the ancestors can easily be understood within the context of the old texts. The “herb” was often used as roof thatch, to cover open doorways, to make rope, and was even an important source of fuel and warmth. In the stories Heather was also often used as bedding or was bundled and used as a pillow.

In the 1911 book Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries by W.Y. Evans Wentz we find Heather used in a very clever manner. This story is of Dermout who has stolen Finn Mac Cool’s Sister:

“He took with him a bag of sand and a bunch of heather; and when he was in the mountains he would put the bag of sand under his head at night, and then tell everybody he met that he had slept on the sand (the sea-shore); and when on the sand he would use the bunch of heather for a pillow, and say he had slept on the heather (the mountains). And so nobody ever caught him at all.”

There’s actually a link between Heather and the Celtic trickster the fox. There’s an old story found in Joseph Jacob’s 1894 More Celtic Fairy Tales. The same tale is found in various other texts as well. The fox would gather some Heather and put his head into the midst of it. He would then enter the stream stealthily, swimming towards the ducks. These unsuspecting birds would attempt to use this Heather as cover, only to find themselves inside the jaws of the wily fox. It would seem that the Fox had a clever use for everything, because he would also carry a piece of wool in his mouth, backing into the flowing water until only his nose and the wool were exposed. He did this in order to rid himself of fleas.

In the 1825 book Fairy Legends of the South of Ireland by Thomas Croker the Cluiricaune knew the “secrets of brewing a Heather beer.” This is not so unusual as Heather was often associated with fairies and magic.

In the 1903 book Heather in Lore, Lyric, and Lay by Alexander Wallace we are told that witches in Scotland would ride over the Heather on black tabby cats during Samhain. According to this text Heather was also associated with the Cailleach; the primordial Celtic hag goddess[v].

In More Celtic Fairy Tales we find another interesting Heather story. A young couple attempts to escape from powerful witch sisters. As they flee they take the form of Doves in order to confuse their pursuers. When the one sister realizes that the birds are actually the escaping couple she comes at them in a fury. To avoid her they turn themselves into Heather brooms and begin to sweep the town square without “the assistance of human hands.” After this inconspicuous act they turn once more back into Doves and resume their flight to safety.

Nothing to see here, we’re just two brooms doing some innocent sweeping… honest.

The Tylwyth Teg -a type of fairy- at certain times of the year lived in the Heather or Gorse[vi]. Heather is not just connected with fairies but is also associated with the dead. As Katherine Briggs says, however, Fairies and Ghosts may be the same thing[vii].

In the 1900 book Celtic Folklore: Welsh and Manx by John Rhys the spirits of family members are often seen dancing over “the tops of Heather.” The herb is even directly connected to a haunted graveyard. We are also told in the same text that if a person heard the fairy songs – and was possessed to dance – that they would often wake the next morning “in the Heather.” The Heather was also connected to fairy rings elsewhere in the book.

In mythology, Heather is associated with Rathcroghan, also called Cruachan[viii]. This is an ancient site found in the Ulster Cycle and is an important archaeological site today. In the 1904 Gods and Fighting Men by Lady Gregory we are told that Finn Mac Cool “delighted” in the song of “the Grouse of the Heather of Cruachan” whose music put him to sleep. Elsewhere in the book we are told that Finn found peace in “the Stag of the Heather of quiet Cruachan.”

Finally, in Joseph Jacob’s 1895 Celtic Fairy Tales we are told of a long forgotten magical use for Heather. In this tale Conall blinds a one eyed giant -who may or may not have been a later version of Balor – with Heather:

“I got Heather and I made a rubber (?) of it, and I set him upright in the caldron. I began at the eye that was well, pretending to him that I would give its sight to the other one, tell I left them as bad as each other; and surely it was easier to spoil the one that was well than to give sight to the other.”

The Foliage:

In Alexander Wallace’s 1903 book Heather in Lore, Lyric and Lay, Heather branches were carried around the sacred fire three times before being raised above dwellings to protect the house’s occupants “against the evil eye.” The text also says that throwing Heather after a person was supposed to bring them good luck.

Robert Ellison relays in Ogham: the Secret Language of the Druids that “a small broom made from Heather can be used to sweep an area where magic is to be performed.” He also says that Heather can be burnt as incense while working with “spells involving the fair folk.”

In A.W. Moore’s 1891 Folk-Lore of the Isle of Man we are also told of a spell that was used to remove evil or the influence of witches from fishing boats:

“It was not only on land that burning some animal or thing to detect or exorcise witchcraft was resorted to, but at sea also, for when a boat was unsuccessful during the fishing season, the cause was ascribed by the sailors to witchcraft, and, in their opinion, it then became necessary to exorcise the boat by burning the Witches out of it. Townley, in his journal, relates one of these operations, which he witnessed in Douglas harbor: in 1789, as follows — ‘They set fire to bunches of heather in the center of the boat, and soon made wisps of heather, and lighted them, going one at the head, another at the stern, others along the sides, so that every part of the boat might be touched.’ Again he says, ‘There is another burning of witches out of an unsuccessful boat off Banks’s Howe— to the top of the bay.’ Feltham, writing a few years later, also mentions this practice.”

In this example, Heather is used in a similar manner to the Native Americans’ who burnt instead Sage or Sweet Grass. This Heather smoke was used to purify the boat and to chase off evil spirits.

“Heather is an Herb Tree in Irish law. It is abundant on heathland throughout western Europe, growing profusely in acid soil.” – Caitlin Mathews (Celtic Wisdom Stick

[i] The Ogham was not originally a Tree Alphabet. See previous posts.

[iii] The Ogham Tract.

[v] The previous Heather post relays more Heather stories taken from this book.

[vi] See last week’s post on Gorse.

[vii] Katherine Briggs says that fairies were categorized as either “diminished gods or the dead.” The Fairies in Tradition and Literature.