“Out of my experience, such as it is (and it is limited enough) one fixed conclusion dogmatically emerges, and that is this, that we with our lives are like islands in the sea, or like trees in the forest. The maple and the pine may whisper to each other with their leaves, and Conanicut and Newport hear each other’s foghorns. But the trees also commingle their roots in the darkness underground, and the islands also hang together through the ocean’s bottom. Just so there is a continuum of cosmic consciousness, against which our individuality builds but accidental fences…” –William James (The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries)[i]

The Roots:

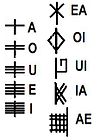

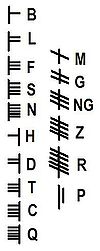

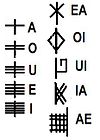

The sixteenth letter of the Ogham is Ailm. This is the Scotch Fir or Scots Pine.

There is a lot of confusion regarding which tree should be assigned to Ailm. The Ogham tract says that it is the “Fir” tree. The Fir tree is also listed within the tract as a possible choice for Gort, the Ivy, as well. Robert Graves named the tree representing Ailm as the Silver Fir based on the mention of the Fir tree within the text[ii]. This choice is generally accepted as being correct.

The first Silver Fir, however, is not believed to have been introduced into neighbouring Scotland until 1603[iii]. The Ogham Tract is from the Book of Ballymote believed to be written in about 1390[iv]. Before the 18th century the Scots Pine was known as Scotch or Scots Fir[v] so the mention of the “Fir” within the Ogham Tract is most likely a reference to the Pine[vi]. The Scots Pine is native to the British Isles and would have been better known in Ireland. Pine is also mentioned within the Ogham tract, but various names for the same tree are found for other letters as well. For example the Yew is also the Service Tree, Blackthorn is also Sloe, and Quicken is also the Rowan. It is likely that both Pine and Fir refer to the Scotch Fir or Scots Pine. The variety of names given for the same species may be a poetic recording or even from the translation by George Calder in 1917[vii].

Firs and Pines -as well as Spruces, Cedars and others- are part of the same family known as Pinaceae. These conifers share a prehistoric heritage as members of the first trees growing in many areas upon the land of our planet. The close relation -and primordial ancestry- make them more akin to one another than many other trees that have

greater differences. For this reason the Pinaceae trees are easily interchangeable, and the choice to honour one above another -within the Ogham list- may feel quite comfortable to many students of the Ogham.

Liz and Colin Murray speak of Ailm as being a few of “long sight and clear vision[viii].” Nigel Pennick –who suggests the few represents the Elm, however- agrees. He adds that Ailm is about, “Rising above adversity” as well[ix].

John Micheal Greer lists the attributes of Ailm as vision, understanding, seeing things in perspective, and expanded awareness[x].

Robert Graves calls Ailm or the Fir, “the Birth Tree of Northern Europe[xi].”

Eryn Rowan Laurie also says that Ailm represents, “origins, creation, epiphany, pregnancy and birth[xii].”

Ailm, the Scotch Fir or Pine, is the tree of new beginnings and clarity of perspective. These ancient trees also seem to represent the Cailleach, the Celtic hag goddess.

The Trunk:

Robert Graves, in the White Goddess, claimed that there was a Gallic Fir goddess named Druantia who was also known as “the Queen of the Druids.” She was also apparently “the mother” of the tree calendar.

I have never been able to find a reference -before Robert Graves that is- that even mentions such an important figure as “the Queen of the Druids”. New age pagans speak of her often enough though, and she even has a page on Wikipedia that references two Llewellyn authors from 2006. As far as I can tell, this goddess is completely fictitious.

Robert Graves’ Druantia is fictitious. Just like his tree calendar that she was supposed to have been the mother of.

Graves proposed that the Ogham was actually a tree calendar and much of the White Goddess is actually a poetic essay supportive of this idea. The calendar starts on December 24th with the Birch tree. Each of the thirteen months of the year continue then as Rowan, Ash, Alder, Willow, Hawthorn, Oak, Holly, Hazel, Vine, Ivy, Reed, and then Elder. His justification is an interpretation of an old Irish poem the Song of Amergin which he believed was a code left for those with poetic sight –him- to find answers within. He reaches into his own interpretations of myths and observations of nature to support these conclusions.

The idea is actually quite beautiful and many people like the idea of an Ogham calendar and have adapted it into their own lives.

Liz and Colin Murray took the idea and ran with it a little further several decades later. They perceived things differently though. They believed that the year would have started at Samhain – Halloween- and so took the same calendar but just made it begin earlier at October 31st. Fair enough. This is truly the beginning of the Celtic year according to most scholars. The justification for many of Graves’ choices however fell short with the Murray’s shift though. It did not make sense, at least as Graves had described it, to have the Hazel/Salmon month in July when the salmon clearly run in fall – as one example.

Since then many have believed full heartedly in a tree calendar. The Ogham was not even really a tree alphabet –as we have discussed many times before- how could it then be a tree calendar?

I don’t see anything wrong with using an Ogham tree calendar, as long as one is aware that it’s not based on historical fact. As long as that individual is not passing on that same information as “the truth” to other seekers then what is the harm in any new shaping of old ideas? Perhaps there is a niche crowd that needs a Fir goddess Druantia just like there seems to be a pocket of people who want to believe in Cernunna the female counterpart of Cernunnos[xiii]?

The problem is that those who seek are often looking for real connection to the past, to the spirits of old, and ultimately to themselves and nature. I know that I felt misled when I began to realize that the teachers of the faiths that resonated most deeply within my soul were just as confused as I was, maybe even more so. They had no real relationship with the spirits they professed to. Why else would they assume that it was okay to make things up about beings that others believed were real and divine even? Was it because there were times that they were unable to find answers, so they decided to fill in the blanks themselves?

The conifers, for example, do not make as many appearances in myth as some of the other trees do.

According to Fred Hageneder in the Meaning of Trees, the Pine had special meaning to the Scottish. He claims that this tree was considered a good place to be buried beneath by clan chiefs and warriors. This is further supported on the Trees for Life: Restoring the Caledonian Forest website. In the ‘Pine mythology’ section Paul Kendall says that the Pine was used as a marker for the burial places of warriors, heroes and chieftains[xiv].

In more folkloric times Pine cones were often used in spells. They were carried to increase fertility, for attracting wealth, money and were also seen as powerful herbs for purification rites and protection spells[xv].

In mythology Merlin climbed the Pine of Barenton in a Breton story, “To have a profound revelation, and he never returned to the mortal world[xvi].” This is revealing as tree climbing appears in various shamanistic traditions around the world.

In the Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries W.Y. Evans-Wentz shares a story about St. Martin and a sacred Pine found in Tours, central France[xvii] that is worth sharing. Apparently, when St. Martin threatened to fell the tree to prove to the locals that it wasn’t sacred, “The people agreed to let it be cut down on the condition that the saint should receive its great trunk on his head as it fell.” St. Martin decided not to have the tree cut down after all!

The conifers -being the trees of the ancient forest- do seem to reach out to us as the Cailleach, the hag or crone aspect of the goddess that speaks to us from the times immemorial. These trees, the Pine, Spruce or Fir, are strong and green even in the midst of winter and were in fact some of the very first trees to climb out of the oceans.

In Visions of the Cailleach Sorita d’Este and David Rankine describe the Cailleach as follows; “Some tales portray her as a benevolent and primal giantess from the dawn of time who shaped the land and controlled the forces of nature, others as the harsh spirit of winter.”

The references in the Celtic myths to the Pine or Fir are indeed sparse. This does not mean that the conifer trees were not sacred, however. As Hageneder reminds us, “The Pine is the tree that features most frequently in the badges of the Scottish clans”. From a culture where symbols are keys to the land of spirit and of the fey, that tells us something indeed.

Though mysterious and illusive, Ailm, the Scotch Fir or Pine, is the tree of primordial beginnings and deep understandings.

The Foliage:

The first trees were actually giant ferns. Then there were palm-like trees called cycad, which still exist in some places today.

Arriving at, “About the same time that the first warm-blooded mammals appeared, the conifers became for millions of years the dominant trees on the planet. Their seeds, contained in distinctive cones, enabled them to dominate the environment and overshadow the spore plants, and to spread into habitats where there had been no previous growth. Today’s descendents of those ancient conifer forests –pines, spruces, firs, larches, cedars, cypresses, and junipers – include some of our tallest trees and the oldest living plants.[xviii]”

Today the Scots Pine is the most widely distributed coniferous tree in the world and a “keystone species for the Caledonia forest[xix].”

The Silver Fir, however, is highly sensitive to air pollution. They are extremely endangered. The last wild Silver Fir tree died in Bavaria Germany only a few years ago[xx].

A great tragedy.

“Go to the rock of Osinn,” said the hag, “where the withered pine spreads its bare branches to the sky. There, as the moon rises, walk three times withershins round the riven trunk, and cast the broth on the ground before her.” – George Douglas (Scottish Fairy and Folk Tales. 1901)

[i] William James is quoted in The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries by W.Y. Evans-Wentz (1911).

[ii] The White Goddess.

[iii] http://www.forestry.gov.uk/forestry/INFD-6UEJ3L

[iv] Oxford Dictionary of Celtic Mythology.

[v] Firefly Encyclopedia of Trees.

[vi] Eryn Rowan Laurie in Ogam: Weaving Word Wisdom, says that Fir and Pine seem interchangeable within the Ogham tract text, most especially the Irish word gius which seems to apply to them both. Her statement seems to support my theory even further.

[viii] Celtic Tree Oracle.

[ix] Magical Alphabets.

[x] The Druid Magic Handbook.

[xi] The White Goddess.

[xii] Ogam: Weaving Word Wisdom.

[xiii] Helmut Birkahn is a German Celtic historian quoted by Sabine Heinz in Celtic Symbols.

[xv] Tree Wisdom: the Definitive Guidebook. Jacqueline Memory Paterson. Etc.

[xvi] Fred Hageneder.

[xvii] This would not be considered a Celtic story due to the time frame and geographical area.

[xviii] The Secret Life of the Forest. Richard M. Ketchum.

[xx] Fred Hageneder.