The Roots:

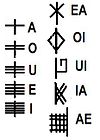

Gort is the common association for the twelfth letter of the Ogham. Gort however does not literally mean ivy, but that of a tilled field. In the scholar’s primer Gort is also associated with green pastures, corn, and cornfields, as well as to ivy[i].

Most do associate Gort with the ivy plant, however. Liz and Colin Murray equate the ivy with the, “spiralling search for self”. Stephanie and Philip Carr Gomm further add to this by saying that the ivy is comparable to the labyrinth in relation to ones personal search through the mysteries of life and death. They also explain that there is a strong association of the ivy plant to the snake, the egg, and to the god Cernnunnos[ii].

Robert Graves calls ivy, “The tree of resurrection”, and in doing so seems likely to agree with the Carr Gomms.

John Michael Greer calls Gort, “A few of tenacious purpose and indirect progress, symbolized by the ivy bush; a winding but necessary path and entanglements that cannot be avoided.”

Where as Eryn Rowan Laurie suggest that Gort is associated with prosperity and growth, Nigel Pennick contrarily reminds us that the Irish word Gorta means hunger or famine which seems to suggest that the letter has a potential dark or shadow side that needs to be considered as well.

Ivy sometimes takes the place of Holly in the battle with the Oak, but in other traditions, like the one of the Jack-in-the-Green-Chimney-Sweeper spoken of in James Frazer’s the Golden Bough, the ivy and the holly may be adversarial as well.

The ivy is associated with the fairy kingdom in many of the Irish folk tales – though usually indirectly. Its comparison with the snake links it with the image of the antlered Cernunnos, who holds the serpent in one hand and the torque in the other. Gort is also associated with the swan in the bird Ogham which is found in the Ogham Tract [iii].

The Trunk:

The ivy is sometimes associated with certain Celtic gods by various authors. There is little, if any, evidence of any of these relations to the gods or goddesses in any of the myths.

There is a trend that can be found in the folk stories of Ireland -as they pertain to the ivy plant- however.

Ivy is often described as being around, or surrounding, the entryways of caves or secret passages -and sometimes even hiding these doorways to the fairy kingdom from the outside world.

A prime example of this is found in the book the Fairy Legends of the South of Ireland by Thomas Croften Croker published in 1825. Despite the misleading title – the stories take place more often outside of Ireland than in it – the account is of the finding of the Welsh hall of Owan (Owain) Lawgoch[iv].

There are other accounts of similar tales regarding Owain Lawgoch found elsewhere, but in this story the main character remains unnamed. This “Welshman” finds a passageway that is obstructed with overgrown ivy. He moves the plant aside and enters the passageway out of curiosity and finds a tunnel that leads into a hall. As with all of the stories of Owain Lawgoch, this is the hall of sleeping warriors, and it is filled with either “one thousand” or a multitude – as in this story – of sleeping warriors in full battle dress. The intruder makes a noise accidently and wakes up the warriors from their slumber (in some stories he is taking gold) who then yell out, “Is it Day? Is it day?” as they rise to their feet. The quick witted Welshman then exclaims, “No, no, sleep again.” The warrior’s then go back to sleep and the man departs.

It may seem like a bit of a stretch to equate the fairy openings in the ground covered with ivy as having any significant meaning, simply from what could be mere descriptive filler. Though ivy is often mentioned around these caves or caverns this does not seem to be enough to be conclusive evidence that ivy is in fact tied to the Otherworld. The tale that does seem to lend itself to these observations, however, can be found in Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms, and Superstitions of Ireland: Volume 1, by Lady Wilde published in 1902. These stories were collected mostly from oral sources. This one is called the Fairy Dance:

One evening in November, the prettiest girl in Ireland is walking to fetch water from a well. Near her destination she suddenly slips and falls. When she stands up again she finds that she is in an unfamiliar place. Nearby there is a fire with people around it so she decides to approach. When she moves into their company she notices that there is one particularly handsome golden haired man with a red sash. He looks at her with adoration, smiles, and asks her to dance. She says to him “There is no music” for she notices that there is no sound in which they can dance to. The man –smiling- then summons the music from an unknown realm and takes her hand in his to lead her in a dance. They dance throughout the evening in which time itself seems to be suspended. The man then asks her to have supper with all of them, the whole group, at which time she notices a stairway that leads beneath the ground.

The pretty girl then leaves with the handsome stranger and the rest of his company, descending into the earth. At the end of the stairs is a bright gold and silver hall with a lavish banquet laid out on a table. She then sits with all of the other people and prepares to eat. A man, one in which she had not previously noticed, whispers in her ear not to drink or eat. He warns her that if she does she will never be able to leave again. Taking this stranger’s advice she refuses to partake in the feast. A dark man from the group stands up and proclaims angrily that whoever comes into the hall must eat and drink. He then tries to force some wine down her throat by holding a cup to her lips.

A red haired man grabs the girl by the hand and leads her away quickly[v]. He places in her hand, “a branch of a plant called Athair Luss (the ground ivy)”. The red haired man tells her to take the branch and to hold it in her hand until she reaches home, that if she does so that no one will be able to harm her.

The whole time she flees, however, she can hear pursuers, even as she goes inside of her home and bars the door. The voices “clamour” loudly outside. They tell her that she will return to them just as soon as she dances again to the fairy music which “Did not leave her ears for a very long time”. She kept the magic branch safely, however, and the fairies never bothered her again[vi].

As a side note, it may be interesting to add that elsewhere in the same book the ivy plant is listed as one of the seven fairy herbs “of great value and power” along with vervain, eyebright, groundsel, foxglove, the bark of the elder tree and the young shoots of the hawthorn[vii].

It would seem that Ivy acts as some sort of a barrier, or gateway, between the worlds.

Although the appearance of Gort, or ivy, is not as overt as that of the more legend dominating trees such as the hazel or hawthorn, it does seem to speak to us from the other side, however.

If ivy is a force between the two worlds, or a doorway of sorts, then how can this symbol be interpreted when the plant itself is wound around another tree like a birch or a rowan, for example? It would seem that there is something for us to learn here, for it appears that the veil is thinner where Ivy grows. In dark garden and forest spaces where ivy seems to flourish the sense of the Otherworld is very strong.

These places, when found, are ones which I like to visit alone.

I will sit in that garden, that evergreen pasture of sweetness, and contemplate my own journey from this realm into the other and back again, through the mysteries of life and death, and as Stephanie and Philip Carr Gomm have said, into “the soul’s journey through the labyrinth.”

The search for self can often lead one into even more hidden realms and strange places.

The Foliage:

The search for self can be found at the core of many spiritual traditions.

The pagan paths are most often attractive to those who seek to know and understand themselves or their relationship to the natural world around them.

Doorways open, rationalizations are made, comparisons to previous learning’s reach out to grab the seeker by the hand, and eventually revelations – both great and small- come forth to reveal themselves to the awakened sleeper.

Who am I then, to criticize the way in which others see the world? Why is it that I am so frustrated by those who half-heartedly reach out to the Ogham as a tool of authority and teaching over the less knowledgeable? Should I not be simply happy that people, teachers if you will, share their personal revelations with others regarding the Ogham and how they see the world?

As I seek to learn who I am, I too have walked upon many paths. I have studied Christianity and been Christian, I have followed and continue to follow the ways of Bushido, and I have sang in the sweat lodge and even eaten the medicine in the church ceremonies in the desert of Arizona. I have sat crossed legged for many hours upon the ground -or upon wooden chairs- trying to learn to properly meditate and to run energy in the traditions many would call Eastern and some would call New Age. I have studied the bardic material of the Order of Bards, Ovates, and Druids and I have learned how to travel in the ways of the shaman. I have read the myths of many nations, the Quran, the Holy Bible, some of the Gitas, the Book of Changes, and many more. Perhaps I too can incorporate all of these paths and what I have learned together in my search for understanding and share them with the world? Should I then make my own Ogham associations to various traditions?

As I have shared before, I first found the Ogham around 1988. I have looked at this material for a very long time, and yet, I still do not see myself as an expert in any way. I have a problem at times identifying some of the trees – especially their wild North American counterparts, I do not speak old Irish, I have never been to Ireland, and I have yet to get a full academic degree which would give me some critical weight -which I would like to possess even for my own sense of self advancement.

Yet there are those that will sell the Ogham and the Celtic gods of old to anyone who will listen simply because they can. They do so because they think they can get away with it and they often do. They know almost nothing of the alphabet, even less about the culture, and clearly do not believe in what they profess to believe in.

In fact, it is apparent to me that they do not believe in those deities they profess to, or in the Ogham as a magical alphabet at all.

If I truly believed in a deity named Brigit I would not profess to another that this unknowable, mysterious, divine, mother was associated with unicorns or herbs from South East Asia when I am clearly the only person who believes this or has found some hidden text that states this. If I truly believed in the Ogham alphabet I would not add my own letters at my own convenience and claim that this was the way that they always were. I would not tell you that the sign of Virgo is such and such a tree and the rune of Tyr is directly related to another.

The Ogham exists within a cultural paradigm. That existence is in relation to the language and culture of the Celts, most especially to the Irish Celts. It is a mysterious and difficult alphabet to understand as there is very little record as to what it was truly used for and how it was used at all, despite various claims.

At one time the Celts were spread out over most of Europe and as far as Egypt. War and the advancement of other cultures leave today only six existing pockets of Celts[viii] and these are found in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, Wales, Cornwall, and Brittany. The greatest body of knowledge that was preserved regarding the Celts was that which was put to paper by the Irish monks.

The history of the Celts is long and bloody. It was not so long ago that the Irish were still being persecuted, and some would argue -with much validity- that they are still being persecuted today. This persecution took place after the Celtic tribes had already been wiped off of the face of the Earth, one after another, by Rome and various later conquerors. This was even after the religion of the Celts was Christianized and later bled out of the people during the witch trials and the religious killings –murders- throughout Europe during the so called religious movements.

The conquest of Ireland by the English had killed over one third of the population of the country. In May of 1654 the remaining Irish were moved to reservations and were only allowed on the West side of the River Shannon. Any Irish found to the East was killed as a rebel and 5 pounds was paid for their head. Irish villages were surrounded and people were gathered up and sent to colonies as labour because they were “cheaper than slaves if they died[ix]”.

Many Irish fled starvation – the price of being over taxed now remembered as a famine- to the Americas to start a new life. Here they were given no quarter either. Beyond overt racism, many of the original penitentiaries in North America, especially those in Canada, were built for the Irish problem[x].

In Ireland there was rarely any peace either. The people often rose up against oppression and struggled for independence. There is much history of civil war, famine, oppression and bloodshed on the Emerald Isle.

The Irish books were burnt first by St. Patrick -in at least one account- and regularly afterwards by various suppressors until relatively recent times. The culture itself was the sufferer of the deliberate persecution of one race that was seen as inferior by another that saw itself as superior. According to Peter Ellis, “Language is the highest form of cultural expression. The decline of the Celtic languages has been the result of a carefully established policy of brutal persecution and suppression…the result of centuries of a careful policy of ethnocide.[xi]”

For many of us, studying things Celtic offers us insight into a relatively recent ancestor that was still in touch with -and lived in close relation to- the earth. The memories of these ancestors can be gleamed through the veil of time, for but a moment, as we look over the myths and legends that show us who they were and who they may have been.

The Ogham alphabet, particularly the tree alphabet, offers the seeker a chance to investigate a system that is at once both mysterious and insightful. The Ogham leads us into the realm of myth and stretches our imagination. It can be found to be logical and mathematical, and has led more than one person into a deeper relationship with nature and the many mysteries that she has to offer. The Ogham can teach us about the Celtic ancestors, about a culture that has almost been lost to history in so many ways, and it may even be used – as it is by many – as a type of resurgent divination.

If one is a spiritual seeker then the Ogham may even bring them into a deeper relationship with the deities, the divine, and ultimately even with themself.

In our search for truth and understanding, let us not forget to leave the trail through the forest in a way in which we found it.

Ancient, powerful, and wise.

Awen.

“I was raised in an Irish-American home in Detroit where assimilation was the uppermost priority. The price of assimilation and respectability was amnesia. Although my great-grandparents were victims of the Great Hunger of the 1840’s, even though I was named Thomas Emmet Hayden IV after the radical Irish nationalist exile Thomas Emmet, my inheritance was to be disinherited. My parents knew nothing of this past, or nothing worth passing on.” -Tom Hayden

[I] http://www.maryjones.us/ctexts/ogham.html

[II] The Druid Animal Oracle.

[III] Ibid.

[IV] An ancient ruler of Britain. This story has a familiar looking theme.

[V] It is implied that the red haired man is the same man that warned her earlier but this is not stated in the tale.

[VI] This story is reminiscent of the Anne Jefferies story previously shared in the Huath (Hawthorn) post.

[VII] This book is of great interest and contains lore along with folk charms and spells. The copy I have acquired is from the link below. It is free to download because it’s no longer in copyright http://www.archive.org/details/ancientlegendsm01wildgoog

[VIII] Usually recognized

[IX] Peter Berresford Ellis

[X] “Recently arrived immigrants were perceived as a threat -as having suspect values and a poorer work ethic.” Canadian Corrections: 3rd Edition. Curt Griffiths

[XI] The Druids