The 25-foot Amanda Anne plows through the frigid February waters of the Juan De Fuca Strait. Somewhere in the darkness ahead of us are the islands habituated by a wolf many in the Songhees First Nation believe is sacred.

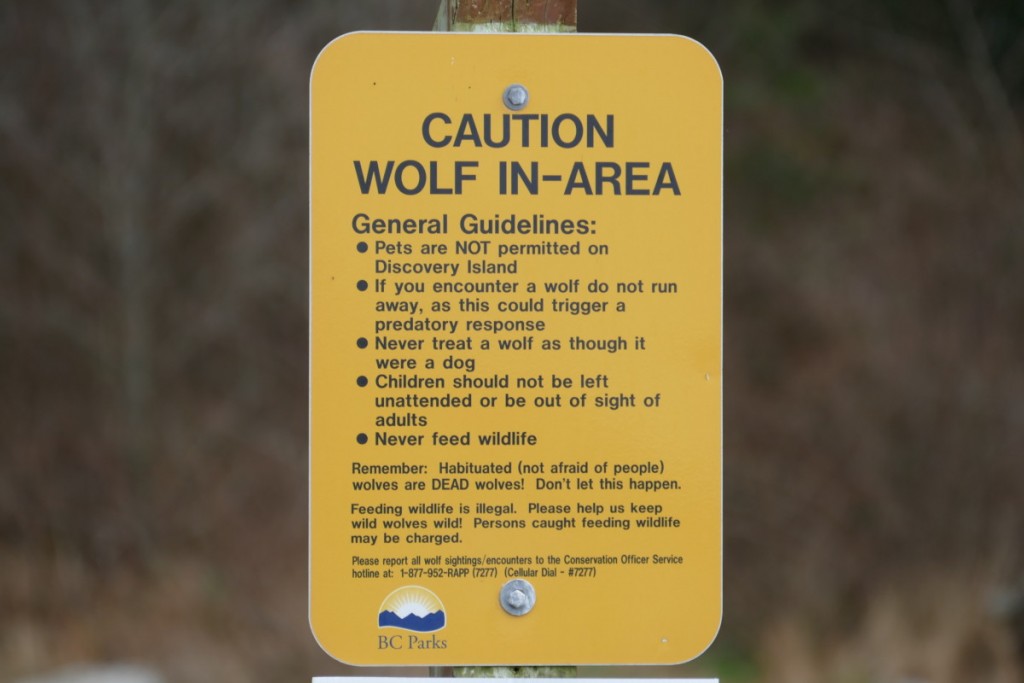

Campers were the first to report a lone wolf on Discovery Island, east of Victoria, in 2012. Conservation officers dismissed the sightings as mistaken identity. Perhaps a dog had been abandoned on the island? While coastal wolves have been known to swim short distances, it seemed unlikely that this one would have swam the five km. from the city of Victoria.

However, Songhees First Nations members and conservation officers have since confirmed that the skittish animal is a coastal wolf. Discovery Island is part marine provincial park, part Songhees reserve land, but the wolf has also been spotted on various other islands nearby, including First Nations reserve lands such as the Chatham Islands. It has been dubbed Staqeya by the Songhees, which means “wolf” in their Coast Salish Dialect.

I was intrigued. How could a wolf exist by itself for so long in such a small area without other wolves? And where did it come from? The nearest wolf pack is in the vicinity of Shawnigan Lake, 44 km. north-west of Victoria. To come from that direction, the wolf would have had to cross multiple heavily populated municipalities and highly trafficked roads before making the swim.

I’ve always felt a special connection to wolves. First Nation members have told me that the wolf is my spirit animal. As a soldier in Afghanistan, I kept a patch of a wolf on my pack. Wolves have a code of honour absent in many animals; they are monogamous, loyal, take care of their sick, and will die for one another. Yet they have been persecuted for thousands of years, often to the point of extinction, out of unsubstantiated fear that they are dangerous. As a veteran, I can relate.

I hope to find evidence that Staqeya is still in the area. Ideally, I would like to get a picture of her along the shore of one of the islands, but failing that, tracks or scat would be revealing as well.

We approach the fog-shrouded islands, and agree that trying to go ashore at night would not be safe. Chief James Swan from Ahousaht (a First Nations village north of Tofino) and I find a semi-sheltered spot to put down anchor until dawn.

I first met James during infantry training in the army. Our friendship is rooted in the belief that the natural world is a spiritual kingdom that deserves respect. When James heard about my interest in Staqeya, he volunteered to take me.

The sound of singing frogs drifts over the water. The air is cold and the stars are bright. It’ll be a chilly night, but a short one.

The sun rises, and the rain, which had arrived in the night, has stopped. The tide rips past us but the water is otherwise fairly calm. We drink our tea and start to sail along the shoreline, looking for signs of Staqeya. Our plan is to search by boat first, as she has most often been sighted from along the shore.

On the water we meet a lone kayaker who claims to have seen the wolf and shows me a picture on her phone to prove it. I recognize the arbutus-lined shoreline and, from news story images, the light-coloured wolf. Staqeya was originally reported to be a female, but the image is of a male. I’m surprised to say the least.

After bidding farewell, we continue on our way. We haven’t seen any signs of the wolf from the water so we head ashore. We find a safe spot to put down anchor once more. The day is still cold but the water has remained calm. James rows a small dinghy towards shore. I travel on my paddleboard with gear on my back.

We land, and I get out of my wetsuit and into my camping clothes. After a short walk, James and I find a bluff where it appears a large mammal has been resting. A trail through the tall grass leads to the spot where the undergrowth has been bent flat to the ground. No large land mammals have ever been reported on any of these islands and pets are not allowed. We are certain that the wolf has frequented this spot recently.

We find some scat in the area as well. Some of it looks several months old, while one sample looks less than a day old.

James has other commitments back in Victoria, and hikes back to our landing spot. We both believe I have a better chance of seeing or hearing the wolf alone. James rows back out to the Amanda Anne, gets aboard, and disappears from sight. He will come back for me tomorrow afternoon.

I’m on the small island alone. From everything we’ve seen so far, Staqeya is here with me.

The wolf mysteriously showed up on the islands shortly before Songhee Chief Robert Sam passed away due to complications from a stroke. Conservation officers originally intended to trap and relocate the animal on the park side of Discovery Island. The Songhees — who had not been consulted — insisted that the wolf be left alone. They issued statements saying that Staqeya’s arrival was directly connected to Chief Robert Sam’s passing. Like me, he had a great love for wolves.

This, of course, defies conventional settler beliefs, but the explanations offered by various officials do also. One conservation officer put forward the idea that the animal had swum from the Olympic Peninsula in Washington, roughly 40 km. away — an impossible distance from a region not habituated by wolves in over a hundred years. Another proposed that the wolf had wandered through the city of Victoria, and still another that it had hitched a ride on a logging barge. As the wolf has demonstrated repeatedly that it is wary of humans to the point of avoiding food-laden traps, none of the theories seem likely.

The Songhees’ belief resonates with me. An island-hopping wolf in the vicinity of Victoria is unprecedented, and by all accounts, Chief Robert Sam was a great man.

I hike the shores for hours. There is sand in only a few places, and mud is scarce. Eventually, my persistence pays off. I find a single paw print clear enough to show up in a picture (slideshow below). I’ve lucked out.

I head back to my campsite to set up my summer tent. My supplies are limited because of weight. I’m tired and the temperature is dropping dramatically. There are no fires allowed on these islands so it is going to be an icy night.

I keep looking in the direction of the bluff James and I had found the impressions on. I see what appears to be a white rock, but I know there hadn’t been a white rock there. The shape is also too big to be a bird. After about 10 minutes, it vanishes like a ghost. I’ve seen Staqeya.

On a small pocket stove, I cook some pasta as day fades to night. There are low clouds instead of stars. The seals on the rocks speak like humans, frogs sing, and an owl calls into the enfolding night, joined occasionally by the haunting howls of Staqeya. The island feels otherworldly and I do not feel alone.

I use my wetsuit as a mat to keep me off the ground inside my tent. I crawl into my sleeping bag still wearing long johns, socks, and my wool hoodie. I make an awkward pillow out of various items as the rain starts to drum against the top of the tent. I dream of wolves.

Morning comes slowly. I rise, make some tea, and pack my gear as the sun comes out and starts to warm me. I lay my gear out to dry as I watch the shoreline and bluff I had seen Staqeya on. It is a beautiful morning.

I pack up, then continue to explore the island. I find more scat. Seal fur and bird bones are abundant. I find scratch marks on a trail as well. Still aware that there are no pets or other animals here, I know I am getting an education in spotting wolf signs in the wild.

The time is approaching for James to pick me up. I head back to our rendezvous point and tighten up my gear. I see the Amanda Anne come into view as James lays on the horn. I throw on my wetsuit and grab my stuff as I head into the water once more.

I find myself reluctant to leave. I feel a kinship to Staqeya and the islands he calls home. I was unable to get a picture of him, but my experience is profound nonetheless. I found tracks, scat, trails, heard him howl multiple times and even saw him in the distance. Four years after he was first spotted on these unlikely islands, the sacred wolf called Staqeya is alive and well, and I take comfort in that.

Special thanks to Spenser Smith and Frank Moher for editing this post.

Beautiful post. But I hope we eventually completely phase out referring to animals as it. Even if that’s not the intention, the connotation is a little derogatory. We should start addressing them as he/she or they, if unsure of the gender. This may seem trivial but I believe it will evoke respect.

Great story on the wolf, and the recent closure of the island. Not sure why some dog owners feel so entitled http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/discovery-island-wolf-1.3769858

What a lovely, haunting tale. I, too, have had an amazing sense of “kindred spirit” with wolves, and admire your courage and tenacity in attempting to see and photograph this elusive being. Living in Esquimalt, perhaps I will be lucky enough to visit the Island myself one day and hear those howls myself. <3

Thank you Trina glad you enjoyed it! Hopefully you do get the opportunity someday. The Northern Lights Wildlife Centre in Golden BC also offers the opportunity to “walk” with wolves if you ever get the chance. Glad to hear of your kinship with wolves. Always nice to meet people who feel the same way 🙂

Beautiful post. I too feel a kinship with the wolf.

Thank you Sue glad you enjoyed it 🙂