The Banshee’s arguably the most famous ghost of them all, and probably the least understood.

“When the Banshee calls she sings the spirit home. In some houses still a soft low music is heard at death.” – George Henderson 1911 (Survivals in Belief Amongst Celts)

There’s an Irish tradition promoting the Banshee as only ever interacting with certain families. Although folklorists have also made this statement in the past, it’s entirely false. The Banshee’s known by many different names, was encountered in many varied forms, and was believed to have existed by a wide array of people[i].

In Ireland, the Banshee is also called Banshie, Bean Si, Bean Sidhe, and Ban Side amongst other names. A great deal of surviving Banshee lore comes from outside of Ireland, however. In Scotland, for example, the Banshee may be referred to as Ban Sith or Bean Shith. On the Isle of Mann she’s called Ben Shee, while the Welsh call her close sister Cyhyraeth[ii].

The she in Banshee, or sidhe, suggests and older source for the stories. The sidhe were the old gods who had fled the Irish invaders to live inside of the hollow hills. They were also known as the Tuatha De Danaan or “the fair folk.”

“Banshee: A female wraith of Irish or Scottish Gaelic tradition thought to be able to foretell but not necessarily cause death in a household.” – James MacKillop (Oxford Dictionary of Celtic Mythology)

In the 1887 book Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms, and Superstitions of Ireland by Lady Wilde, we’re told that the Irish Banshee was more likely to be beautiful, while the Scottish Banshee was more likely to appear in the image of an older crone-like woman. Like most things in Celtic lore, however, this wasn’t always consistent.

The Banshee would usually warn of death by: wailing, appearing as an apparition, playing or singing music, tapping on a window in the form of a crow, be seen washing body parts or armor at a stream, knocking at the door, whispering a name, or by speaking through a person that she had already possessed – a host or medium[iii]. The noble families of Ireland generally viewed the spirit’s attendance as a great honour. Some sources do say that the Banshee served only five Irish families, but others say that several hundred families had these spirits attached to them[iv]. The five families usually stated to have had Banshee attendants are the O’Neils, the O’Brians, the O’Gradys, the O’Conners, and the Kavanaghs. Many stories, however, are of other families.

The Ó Briains’ Banshee was thought to have had the name of Eevul[v], or Aibhill as she is called in the book True Irish Ghost Stories. Likewise, a great bard of the O’Connelan family had the goddess Aine (sometimes called Queen of Fairy), attend him in the role of a wailing Banshee in order to foretell – and honour – his death[vi]. Cliodhna (Cleena) is a goddess-like Munster Banshee, who people claimed was originally the ghost of a “foreigner.” Most Banshees remained nameless, however.

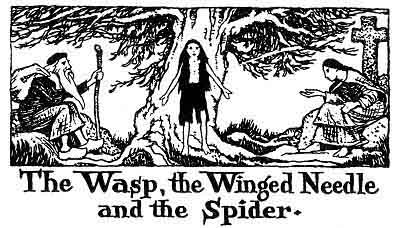

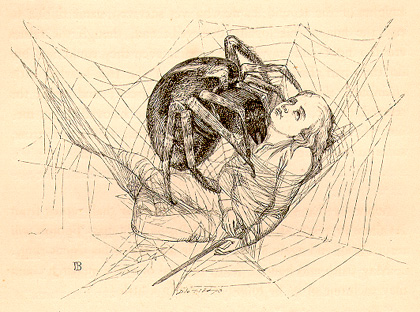

The description of the Banshee varies a great deal throughout the many accounts. If she was young she often had red hair, but she could have “pale hair” as well. She was often described as wearing white, but sometimes she could be seen wearing green or other colors such as black or grey. Red shoes were sometimes mentioned, but so was a silver comb,[vii] which she either ran through her hair or left on the ground to capture some curious passerby. Most described her eyes as being red from crying, or keening, or to be menacing and evil looking. The eyes were also often said to be blue. In J.F. Campbell’s 1890 Popular Tales of the West Highlands, the Banshee was said to have webbed feet like a water creature. Sometimes she was wrapped in a white sheet or grey blanket – a statement that reveals an older funerary tradition and a possible source for the modern white sheet-ghosts of Halloween.

In True Irish Ghost Stories we’re told that the Banshee could not by seen by “the person whose death it [was] prognosticating.” This statement is not consistent with all of the stories either:

“THEN Cuchulain went on his way, and Cathbad that had followed him went with him. And presently they came to a ford, and there they saw a young girl thin and white-skinned and having yellow hair, washing and ever washing, and wringing out clothing that was stained crimson red, and she crying and keening all the time. ‘Little Hound,’ said Cathbad, ‘Do you see what it is that young girl is doing? It is your red clothes she is washing, and crying as she washes, because she knows you are going to your death against Maeve’s great army.’” – Lady Gregory 1902 (Cuchulain of Muirthemne – retelling of 12th CE)

The Banshee – who’s often said to have her roots in stories of Morrigan the Irish war goddess[viii] – could also follow families abroad. One famous story regarding the O’Grady family takes place along the Canadian coastline where two men die[ix]. St. Seymour shares another tale in which a partial Irish descendent sees a Banshee on a boat in an Italian lake. In Charles Skinner’s 1896 Myths and Legends of Our Own Land we’re also told of a South Dakota Banshee living in the United States.

The Banshee could also be a trickster of sorts. She was said to mess with “the loom” in Alexander Carmichael’s 1900 Carmina Gadelica. There’s even a blessing in the section, which is chanted over the item. In W.Y. Evens-Wentz’ 1911 Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries we’re told of a Banshee who could be placated by giving her barley-meal cakes on two separate hills. This action reminds us of the tithes often left for other trickster fairies, and doesn’t seem to be a customary gift one would leave for a ghost. As Katherine Briggs once said[x], however, fairies fall into two categories, “diminished gods and the dead.” Unfortunately, our modern conception of fairies does little to remind us that either one of these forms would be considered as a spirit-being today. As Evans-Wentz further explains:

“It is quite certain that the banshee is almost always thought of as the spirit of a dead ancestor presiding over a family, though here it appears more like the tutelary deity of the hills. But sacrifice being thus made, according to the folk-belief, to a banshee, shows, like so many other examples where there is a confusion between divinities or fairies and the souls of the dead, that ancestral worship must be held to play a very important part in the complex Fairy-Faith as a whole.” – W.Y. Evans-Wentz 1911 (Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries)

The Banshee being attached to a certain family could be extremely beneficial and would have not been seen as a negative. As already stated, any family would’ve been seen as extremely important if a Banshee (or several) attended them. In George Henderson’s 1911 Survival in Belief Amongst Celts, a Banshee, or Maighdeann Shidhe, even gave the “Blue Stone of Destiny” to the Scottish hero Coinneach Odhar. In return for favours, however, it would’ve been extremely important to honour these spirits whenever possible, either out of respect for the Banshee, or from a place of fear in order to placate them.

In modern times, the Banshee became associated more and more with evil. As a portent of death she shared many things in common with the approaching Carriage of Death, the death candles, Ankou[xi] or even with the Grim Reaper. In her more ancient visage, she could easily be compared to the Norse Valkyrie (as the Morrigan often is) or to any other Shieldmaiden whose task it was to collect the dead[xii]. To the commoner of modern times, such a role was reserved for the Angels of God and for the Holy Church alone.

Furthermore, the Banshee – like other mystic beings of Celtic lore – was also able to appear in various non-human forms. A fact which would later make her seem in league with the devil:

“The Banshee is dreaded by dogs. She is a fairy woman who washes white sheets in a ford by night when someone near at hand is about to die. It is said she has the power to appear during day-time in the form of a black dog, or a raven, or a hoodie-crow.” – Donald MacKenzie 1917 (Wonder Tales From Scottish Myth & Legend)

Whether the Banshee does, or ever did, exist is a matter of conjecture. One thing is certain, however, the most famous ghost of them all is the one in which few people actually know anything about. The Banshee was more than a shrieking omen of death. In fact, individual Banshees appeared and behaved quite differently from one another in different stories. Her attachment to a particular family was a relationship that was embraced by the Celtic people with pride, and with honour. Her haunting of a particular place, on the other hand, was met with wary bribes. An unknown Banshee – like a stray dog – could have been seen as something quite different altogether. It would have been this Banshee that brought with it fear – which was usually seen as nothing short of a greeting from death itself.

The Banshee in Celtic folklore seems much more interesting, when we realize that many of our modern ghost stories share the exact same elements. A deceased female relative forewarning death, a disembodied voice, a spirit attached to a particular family, or a haunted landmark may not seem to have anything to do with a Banshee today, but none of these stories are really all that different from the old ones at all. Like it or not, in modern folklore the Banshee still remains. It’s only our terminology that has changed.

[i] James MacKillop. Oxford Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. 1998.

[ii] (ibid)

[iii] St. John Seymour and Harry Neligan. True Irish Ghost Stories. 1914.

[iv] James MacKillop. Oxford Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. 1998.

[v] Thos Westrop. Folklore. 1910.

[vi] W.Y. Evans-Wentz. The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries. 1911.

[vii] This may be an overlap with the mermaid, which history likewise seems to have forgotten was also a spirit.

[viii] James MacKillop. Oxford Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. 1998.

[ix] This would most likely be referring to the east coast but could also be the west coast, as well.

[x] Katherine Briggs. The Fairies in Tradition and Literature. 1967.

[xii] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shieldmaiden