On July 21st, I was in the Cowichan Valley for the filming of Harold Joe’s new documentary, Tzouhalem. Produced by Les Bland Productions and by Harold himself, the film will attempt to unpack the oral stories and urban legends surrounding the near-mythic figure of Chief Tzouhalem, who Mount Tzouhalem is named after.

What makes this project unique is that Harold is a Quamichan traditional Gravedigger. The Quamichan Nation acknowledges the existence of human and nonhuman spirit entities, so strict protocol is observed during funerals in order to avoid problems with either. Harold’s role often calls upon him to repatriate human remains and to help disembodied ancestors find peace.

Chief Tzouhalem had a complicated relationship with this same spirit world. So who better to investigate the legends surrounding him than someone familiar with his teachings? Tzouhalem was a member of the nation Harold is, as well, which means Harold has access to oral histories no other investigator would ever be able to acquire.

Tzouhalem was likely born sometime before 1820. He was at the Battle of Hwtluptnets (Maple Bay), which took place around 1840 (later dates are sometimes given, but these ignore the waves of settlers who had arrived and would have reported). Tzouhalem also participated in the 1843 attack on Fort Victoria.

According to Harold, Tzouhalem led this Indigenous “armada” (as it’s been called) on both occasions. Table 2 of the paper “The Battle of Maple Bay” by Bill Angelbeck and Eric McLay lists Tzouhalem as a “named” Cowichan warrior present in the oral histories.

Tzouhalem brought terror to the Salish Sea until he was killed on Penelekut Island in 1854. Used to getting anything he wanted, he had tried to take a woman there by force. She grappled with him until her husband cut off his head. Live by the sword, as they say.

As some of you know, there’s a whole chapter in The Haunting of Vancouver Island about Chief Tzouhalem. Writing this made me nervous as the stories are gruesome. This is the often unfairly the case with many ghost stories about nonwhite people. Using almost entirely Indigenous sources, it was still a less-than-favourable portrait of the man. But even Tzouhalem’s ancestors claimed he was–and still is–terrifying.

In life, Chief Tzouhalem used cannibalism in order to appease spirits that would assist him in battle. According to sources quoted in my book, this practice was unusual for Coast Salish people. Recorded oral histories from as far back as the 1930s claim Tzouhalem kept a snake in his hair as a familiar. This was the being he had acquired through power seeking somewhere on Mount Tzouhalem.

In death, Tzouhalem went on to haunt the mountain that would eventually bear his name (literally or figuratively) and other nearby locations. Stories are mostly secondhand, but there are parallels between his legend and those of vampires in Eastern European lore.

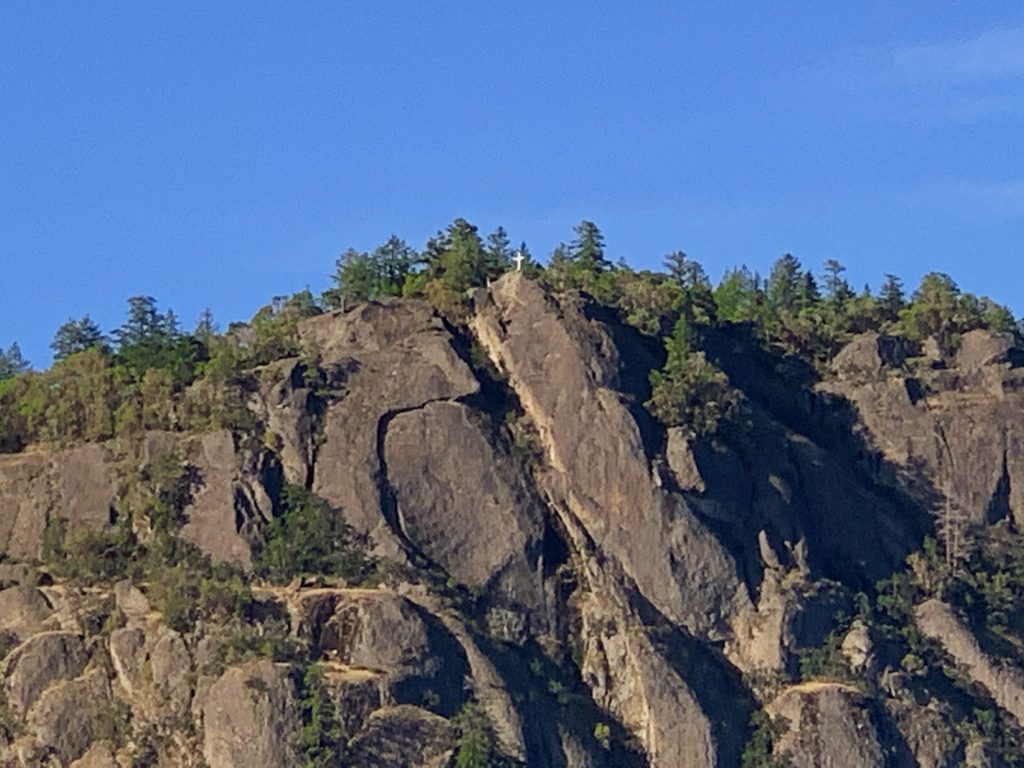

The church eventually raised a cross (date unknown) at the top of the cliff where Tzouhalem is said to have thrown priests, wives, and adversaries off as sacrifices and/or punishment. The cliff face’s history hasn’t been forgotten, so it’s likely that the cross had some exorcism considerations as well as colonial ones. The cross was often vandalized and knocked down over the years. A vote in 2015 determined it would be erected once more. Even non-Christian Quamichan voted in favour of keeping the cross. Goth as hell.

I’ve read firsthand accounts where people claimed they felt watched and followed while hiking near certain sites on the mountain. I’m not sure if Harold plans on sharing these exact locations. It might attract the wrong kind of attention, but it would be interesting to see the caves as Harold shared the oral history associated with them.

I won’t give more of the story away. Harold’s documentary will include content never shared before, including Elder interviews and historical documentation. It was an honour to have been included, considering how little I know compared to community members.

First Nations studies and Elder teachings have taught me it’s important to tell Indigenous stories with as much respect as possible. Since The Haunting of Vancouver Island was published, I’ve been researching ghost stories involving people of colour for future use. When I notice a ghost story can be construed as negative, I will attempt to deconstruct it.

Common examples of ghost story racism includes “Indian” burial grounds (either made up or irrelevant), dancing Indigenous princesses or chiefs, seductress enslaved women, sacred teachings like Voodoo or medicine people used to represent evil, and–of course–the savage killer. Like other old-fashioned narratives, inappropriate retellings are not something a person might notice until it’s pointed out. But I’m young enough, I like to think, that I should know better. I feel I have a sacred duty to the ancestor spirits to point this racism out. This outlook is likely why I was invited to participate in the documentary.

The first part I was involved in took place inside the old Stone Butter Church with Mount Tzouhalem in the background. It was a fitting location as the church is said to be haunted.

Stone Butter Church (archive images) was built in 1870 on Comiaken Hill, in the shadow of Mount Tzouhalem. There had been a church-run Indigenous school here from 1858-1874. Indigenous labourers are said to have been paid in butter, hence its name. The church operated for ten years and then fell into disrepair. There were restorations in 1922, 1958, and 1980. Eventually, the building gained a reputation for being haunted.

Ripley’s Believe it or Not published a sensational story about the old church in 1931. They claimed the original builders had disappeared and that Indigenous people wouldn’t go near it. This was a fake story. Even to this day, there are homes across the road.

Historian T.W. Paterson says the church was abandoned after the more centrally located St. Ann’s Church was built. This move was due to an uncertain land title. Historian John Adams said Stone Butter Church had been built on disturbed “sacred sites” but this is not correct (according to Cowichan sources and a lack of archeological evidence).

The graveyard was in use while the church was, possibly longer. At least some–if not all–of the remains are still in place. For an Indigenous historical account of the church’s history please read Coast Salish artist Joe Jack’s post.

Stone Butter Church has had a reputation for being haunted ever since the Ripley’s Believe it or Not story was published. There could have been preexisting stories, but I haven’t come across any. According to Harold’s testimony alone (read on), there have been specific accounts–or claims–for at least fifty years.

One story circulated online a decade or so ago. A photographer (if I remember correctly) had been followed home from the church by an entity. His home became haunted as a result and the spirit was difficult to get rid of. I remember watching his videos, but can’t recall who it was (if anyone else does). I could be getting his story mixed up.

Stone Butter Church increased in popularity and was vandalized more and more often over the years. Aspiring ghost hunters and psychics were followed by waves of thrill seekers (or maybe it was the other way around). According to Harold, this eventually led to at least one firearm incident. A Quamichan man living across the road had asked partiers to leave. They said, “no” and one of them pulled a gun on him. The Quamichan man went into his home and got his own firearm for protection. Thankfully, no one was hurt.

Understandably, the site is now off limits to non-Quamichan people unless permission has been granted. It says here that this is usually given upon request. I can’t imagine–at least not anymore–driving past all those “Private Property” signs in order to take a photo or investigate without asking permission first (let alone party or spray paint!).

Harold says there really is a haunting here. The spirit(s) are associated with the graveyard and not necessarily the church.

When Harold was young, he was playing a sort of hide-and-seek one night with some other boys. Harold chose to conceal himself amongst the long grass in the graveyard beside the church. At one point, he looked up and he saw the silhouette of a dark-clad man seated upon a horse. The rider did not have a head.

Harold later confessed this to an adult, who scolded him harshly. They confirmed there were spirits in the graveyard by their reaction. It was not good, Harold was told, to play where the dead were trying to sleep.

I should have asked Harold if this incident had anything to do with him becoming a Gravedigger, but I didn’t think of it at the time. Honestly, I was blown away. I had never heard a firsthand account of a headless horseman apparition on Vancouver Island before, or anywhere else for that matter.

I asked Harold if I could share this story and he said that I could. Hopefully I got it right. A caveat of being told Indigenous stories is that they are usually not to be shared without permission. I’ve received this instruction repeatedly from Indigenous storytellers and during Recording Oral Histories field school at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks. Younger people will sometimes say, “I don’t own this story,” before sharing it with me. Meaning, I do not have the right to retell the story without asking permission first. Some communities are more open to sharing than others, but sometimes it depends on the individual. It might be a matter of whether something is considered sacred or not.

I believe my part in the documentary is somewhat small. I was asked to recount Tzouhalem stories that I’d told in The Haunting of Vancouver Island. I was also asked to speak about BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour) ghost stories and some of the considerations and problems surrounding them. Why sources need to be used in order to distance oneself from racism, to show respect, and to avoid appropriation.

If deconstructing racism in ghost stories sounds a little killjoy, consider that Victoria–BC’s capital–has a thriving ghost tour industry, supported by government and businesses, where murderous nonwhite ghosts are status quo. There are also more false claims of Indigenous burial grounds in Victoria than anywhere else I know of. These types of stories are especially problematic in a predominantly white, Christian, community (over 80% are European). These narratives are of actual people who once contributed to our city or who became victims of it. Their lives have been intentionally made into caricatures for profit.

When a racially charged story has emerged organically, it will illustrate the white community’s feelings about that minority culture. In North America, nonwhite ghost stories told by white or non-local Indigenous tour guides almost always add sensational false histories like suicides, murders, seductions, and so on. Sources are often omitted intentionally for this reason or to hide a lack of research.

If you are interested in learning more about deconstructing nonwhite ghost stories, check out Phantom Past, Indigenous Presence, Tales From the Haunted South, and The National Uncanny–all have multiple further sources. The first of these books is a University of Nebraska publication. Two pages of the introduction are about BC Indigenous stories. Most of these are historically inaccurate. It’s embarrassing.

As counterintuitive as it might sound, deconstructing ghost stories actually makes them more interesting. When sensationalism is stripped away, all that’s left is the actual mystery and root account (often historically documented) or the urban legend that started it all.

Speaking of professionalism, I thought the film crew were really dialled in. Script Supervisor Sophie and Production Assistant Bonnie both told me they had taken Creative Writing courses at the University of Victoria. Jes, the sound guy, shared a story at one point about a man who claimed to have had alien contact, or to have been abducted or something. The details came across as both unsettling and hard to dispute. The directer and cameraman Gavin didn’t speak very much but I liked him too. He was intense and focused, but not in a “don’t fuck this up” sort of way. I feel Tzouhalem will be a success based on the crew alone.

If you’re wondering what I could possible know about films, well, probably not much. I was a security manager for a few movie shoots and commercials at the Bay downtown in Vancouver on films like Blade 3 and Elf. I was never involved in a documentary and have only become a person interesting enough to interview a few years ago. But, I do get a sense for things sometimes (even when there isn’t multiple food trucks and crowd control).

I was told to stand inside a pentacle during filming. I don’t think I’ve ever told a ghost story standing in a pentacle, let alone while the sun was setting from inside a haunted church. When I made a joke about this, one of them told me this was the part where they were about to pull up their hoods and pull out daggers. True love, I’m telling you.

I had invested in new shoes and dressed less criminal than normal. I also decided it was time to dye my beard. It had gotten pretty grey during the lockdown and I wasn’t sure how I’d feel if I shaved it off right before getting in front of a camera. The documentary could be in an archive or library (online) a hundred years from now. Gotta represent.

As the sun set, it was time to move to our second location. I took the above photo with the Salish Sea and Salt Spring Island–where I had a reading last fall–in the background.

The second site was on the banks of the Cowichan River. The Stone Butter Church looks blurry from this distance as I was using the zoom on my phone. But you can see the building’s elevation better from this angle and get a sense for how it must have looked back in the day.

After walking along the shore of the river for a few minutes, the crew set up near a fire Harold was building. This was close to the water as Gavin wanted to get the river in the background.

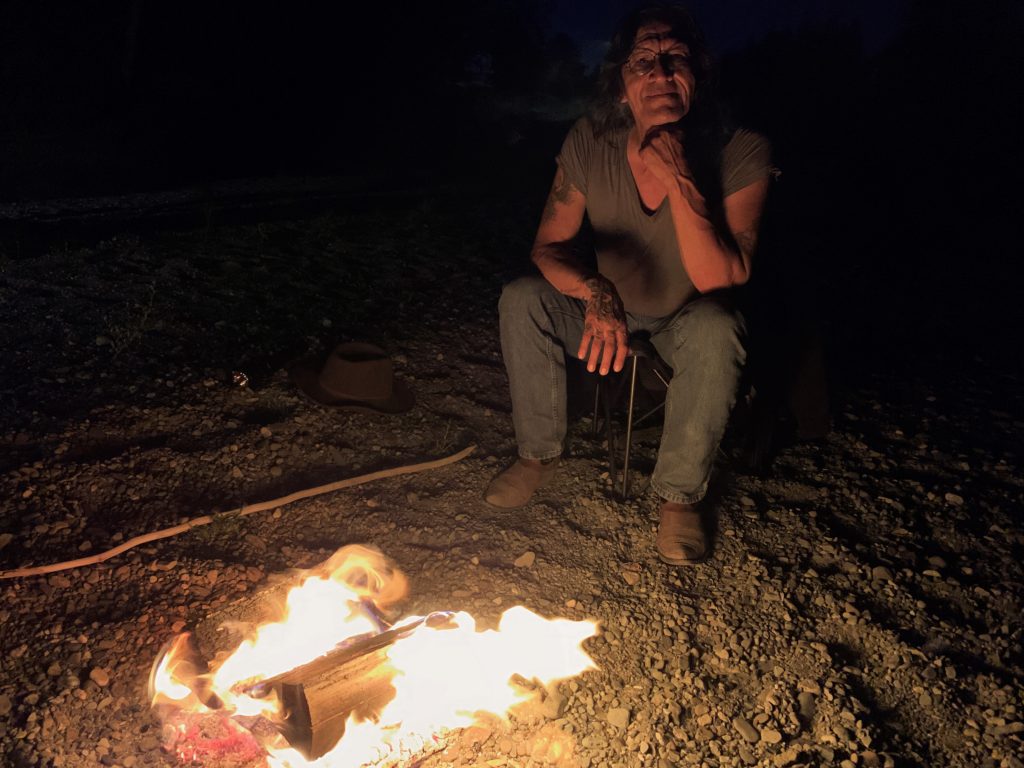

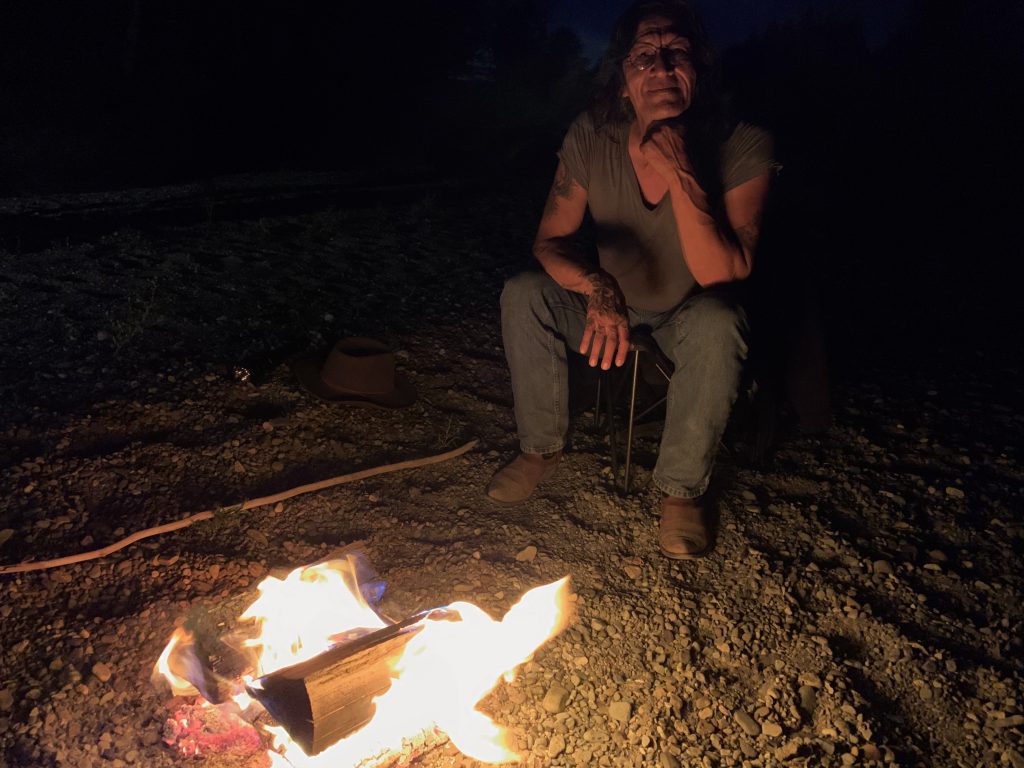

For this part of the film, Harold and I exchanged ghost stories beside the fire and had a more-or-less unscripted conversation. The header photo and the photo below are almost identical, but if you look closely the fire is different. By the time I took them, we had already finished filming. Harold and I had spoken for quite a while. I’m sure some of our conversation will end up in the documentary.

I couldn’t have imagined a more awesome experience than sitting by a fire with Harold Joe and listening to his stories. The crew were silent eyes hovering in the darkness. The bats whirred above us in predatory dance, the river whispered excitedly as it neared the sea, and the fire crackled while spitting cottonwood smoke out into the night.

I wanted to just sit and listen, more than speak. Who was I to tell Harold Joe what Shanon Sinn had heard about Chief Tzouhalem and the legends surrounding him? But I had already expressed this anxiety when I’d initially spoken to Sophie and Leslie of Less Bland Productions during a conference call. They told me that more voices are better in a documentary than one person’s alone would be. It was a fire I’ll always remember.

The conversation was mostly natural, with Sophie asking an occasional prodding question. The time passed quickly. Harold and I talked long enough I probably said something embarrassing if it ends up in the film. But, I did pray and smudge before I arrived on set. I was grateful to be there and conducted myself with as much respect as I was able to.

I did not feel as if the two of us were alone by that fire beside the Cowichan River. On the land used by Harold’s people for thousands of years. The actual ground Chief Tzouhalem had once walked upon, protected, terrified, and maybe even continues to haunt to this day. When the documentary comes out, I will be searching the shadows for things unseen.

I won’t know for a while when or where the film will be available. I’ll share more when I do. In the meantime, if you’d like to know more about Harold Joe and Less Bland Productions here’s their last documentary: Dust N’ Bones. I was told Tzouhalem–likely a working title-–will be full length (longer). I expect it will be of a similar high quality.

Very interesting Shanon. I just happened to be doing a quick google research on Stone Butter Church after it came up in a conversation about potentially haunted spots locally. I was glad to see your name and face come up in connection to it for a perspective I feel I can count on. Hopefully you are well.

Hey Alasdair! Stone Butter Church has its own section in the Haunting sequel I’m working on: The Haunting of British Columbia: Sea Lore and Ghost Stories. I hope you and your family are doing well and that you are writing lots. Zoe McKenna is one of the editors of our latest anthology, That Witch Whispers. Delani Valin has a story in it too. We have a book launch October 30th if you are in Victoria that evening. I rarely use Meta SM anymore, but I’d love to hear what you’ve been up to sometime. If you don’t have my email or number let me know and I’ll send them to you.

Hi Shanon,

I am doing well. My kids are all getting pretty big and they keep my hands pretty full.

I am still chipping away at my old witchy/ detective novel, but progress has slowed right down. I have recently decided that writing a few shorter stories might get the creative juices flowing again. Halloween always provides a little inspiration as my leanings are towards the supernatural or spooky.

I’m glad you’re doing so well. It sounds like you have some good team members at play. I’d love to catch up sometime but I’m not sure if I could make the 30th. (Perhaps?)

Anyway, I do still have a number for you that may or may not be up to date. I’ll shoot you a text and see.

Alasdair

Nice! I’m glad to hear you are still writing — and cool things too! Hopefully you can make it on the 30th. If not, I’m looking forward to talking by some other means. Nice to hear Halloween is still inspiring 🙂

The movie is now available for limited showings: https://livinglibraryblog.com/tzouhalem-movie/

I look forward to the movie and another visit to Salt Spring for you! The reverence that you approach your work with is palpable and I am grateful for your ability to deconstruct the racism in so many of these tales. Bright Blessings on your continued work!

Thank you Maggie! I’m looking forward to visiting Salt Spring Island again too — as there’s a lot more for me to explore.

As for the deconstruction I am enjoying it but I do have my work cut out for me. Many people don’t see a problem with the Indigenous Burial Ground mythos especially, but it’s a tainted ground latent belief that suggests nonwhite nonChristians are evil by default and that they don’t ascend or find peace after passing. From Hollywood to government sponsored ghost tourism, it’s a problem I hope to increasingly address.

What a fascinating story!!

Glad you enjoyed it! I’m looking forward to seeing the other interviews in the documentary. I might have to add a part two 🙂

Yes, I did!! I find such most interesting.

Very much! I find such most interesting 😉