“Alder is one of the most sacred primal woods. Its wood is associated with the British divinity Bran the Blessed, who goes down into the Underworld and becomes the oracular

mouthpiece of the ancestors.” – Caitlin Mathews (Celtic Wisdom Sticks: an Ogam Oracle)

The Roots:

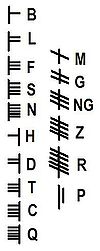

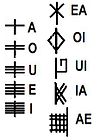

The third letter of the Ogham is Fearn the Alder tree.

The Ogham tract word-associations[i] state that the Alder is the “shield of warrior-bands” and “guardian of milk.” John Mathews in the Celtic Shaman interprets these poetic reflections as being references to “defence.”

Robert Ellison in Ogham: the Secret Language of the Druids calls the Alder the “Battle Witch.” He states that the Alder is associated with guidance (through its connection with

Bran the Blessed), protection and oracular powers.

Caitlin Mathews calls the Alder the “protection of warriors” in her book Celtic Wisdom Sticks. She also associates the tree heavily with the concept of action.

Fearn, the Alder, is strongly associated with Bran the Blessed. The tree is often used for protection and divination purposes. There are many suggestive references in Celtic mythology that the warrior class[ii] had an especially sacred bond to the water loving tree.

The Trunk:

“The alder trees, the head of the line, formed the van. The willows and quicken trees came late to the army.” – The Battle of the Trees[iii]

In a later short text, also confusingly called the Battle of the Trees, we are given more information involving the above epic battle than is found in the original version. Amaethon has stolen from Arawn – a ruler of the Underworld – a white deer and dog(sometimes also a lapwing[iv]) which results in an epic otherworldly battle. Amaethon enlists the aid of his brother, the great god of the Welsh druids, Gwydion along with Lleu. This appears to be a wise decision as Gwydion summons an army of trees to fight the hideous creatures of the Underworld.

There is one warrior amongst the ranks of Arawn who cannot be defeated, however, unless his name is properly guessed by his opponents. Gwydion [v], noting that this mighty warrior bears “sprigs” of Alder upon his shield, is able to guess the strangers name correctly.

“Sure-hoofed is my steed impelled by the spur; the high sprigs of alder are on thy shield; Brân art thou called, of the glittering branches!

“Sure-hoofed is my steed in the day of battle: The high sprigs of alder are on thy hand: Brân . . . by the branch thou bearest has Amaethon the Good prevailed!”

Thus Amaethon and Gwydion are able to prevail over Arawn and Bran securing the use of deer and dogs for men. This battle has been compared to other versions of gods versus titans found in various world religions including the Tuatha De Danaan vs. the Famorians found in Irish myth and the Aesir vs. the Vanir found in Norse Myth[vi].

In one of the riddles of Taliesin it is asked “why is the Alder purple?” The answer to this question is then given as “because Bran wore purple[vii].” It should be noted that there may be a deeper riddle here, as Alder can hardly be described as being a purple tree. There are clues, however, to the possible deeper use of Alder in magic when one considers the tree itself. “Male catkins give a purple tinge to the crowns (of the Alder tree) in January and open dull yellow-brown from February to April[viii].”

The mythology of Bran is very well known. He is sometimes described as a giant. He was capable of wading across the waters between modern day England and Ireland when his sister was dishonoured by her husband, an Irish king. In the ensuing battle that followed, the outnumbered Welsh were able to hold their own through the use of the Cauldron of Rebirth. This magical item brought the dead back to life. The cunning instigator of the whole battle put himself, while still alive, into the cauldron destroying the artefact and himself in the process. Although the Welsh eventually win the battle, Bran is wounded by a poisoned spear (some say he is the first version of the Fisher King) and most of his men are killed[ix]. He subsequently orders these remaining men to cut off his head and to bring him home (or his head at least). Back in Wales, the head hosts a great feast in an underground banquet hall for seven years where he sings and divines the future. This ends when one of the men opens the door to the outside world. Bran’s head finally dies.

Bran’s head was then buried at the White Hill, which he had requested, where the later Tower of London was erected. It was said that Bran would protect the land forever from foreign invaders as long as his head remained undisturbed. It is said that Arthur once dug up the head, resulting in the invasion of what would later become England[x].

(Gundestrupkarret. Photo by Malene Thyssen)

Jacqueline Memory Paterson in Tree Wisdom: the Definitive Guidebook says that the Alder and the Willow are the “king and queen” of the water. This is an interesting statement because the Alder is also said to have a relationship with the Rowan tree, which is the other tree found beside it in the Tree Ogham.

In Lady Wilde’s 1887 collection of Irish folklore titled Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms and Superstitions of Ireland we are told that a branch of Alder over a crib will protect a baby boy from being abducted by fairies. A branch of Rowan will protect a baby girl from the same predicament. According to Wilde this was probably due to the “ancient superstition that the first man was created from an Alder tree and the first woman from the mountain ash (Rowan)[xi].” Elsewhere in the text the Alder is also described as “possessing strange mysterious properties and powers to avert evil.”

There is one more mention of Alder in Celtic mythology, though somewhat peripheral, that is worth sharing. Although Alder may play only a small role (or does it?) the tale is also mentions the Ogham in an interesting context.

Lady Gregory’s 1904 Gods and Fighting Men was hailed by W.B. Yeats as being “the best (book) that had come out of Ireland” during his lifetime. In her retelling of the third and first cycles of the mythical histories of Ireland we are left with one of the most mysterious passages – in my opinion- regarding the Ogham and the secrets of the lost knowledge to be found anywhere. The character of greatest interest is a “fool” named Lomna who is also an initiate of the secrets of the Ogham.

“FINN took a wife one time of the Luigne of Midhe. And at the same time there was in his household one Lomna, a fool. Finn now went into Tethra, hunting with the Fianna, but Lomna stopped at the house. And after a while he saw Coirpre, a man of the Luigne, go in secretly to where Finn’s wife was.

And when the woman knew he had seen that, she begged and prayed of Lomna to hide it from Finn. And Lomna agreed to that, but it preyed on him to have a hand in doing treachery on Finn. And after a while he took a four-square rod and wrote an Ogham on it, and these were the words he wrote:

‘An Alder snake in a paling of silver; deadly nightshade in a bunch of cresses; a husband of a lewd woman; a fool among the well-taught Fianna; heather on bare Ualann of Luigne.’

Finn saw the message, and there was anger on hint against the woman; and she knew well it was from Lomna he had heard the story, and she sent a message to Coirpre bidding him to come and kill the fool. So Coirpre came and struck his head off, and brought it away with him.

And when Finn came back in the evening he saw the body, and it without a head. ‘Let us know whose body is this,’ said the Fianna. And then Finn did the divination of rhymes, and it is what he said: ‘It is the body of Lomna; it is not by a wild boar he was killed; it is not by a fall he was killed; it is not in his bed he died, it is by his enemies he died; it is not a secret to the Luigne the way he died. And let out the hounds now on their track,’ he said.

So they let out the hounds, and put them on the track of Coirpre, and Finn followed them, and they came to a house, and Coirpre in it, and three times nine of his men, and he cooking fish on a spit; and Lomna’s head was on a spike beside the fire.

And the first of the fish that was cooked Coirpre divided between his men, but he put no bit into the mouth of the head. And then he made a second division in the same way. Now that was against the law of the Fianna, and the head spoke, and it said: ‘A speckled white-bellied salmon that grows from a small fish under the sea; you have shared a share that is not right; the Fianna will avenge it upon you, Coirpre.’ ‘Put the head outside,’ said Coirpre, ‘for that is an evil word for us.’ Then the head said from outside: ‘It is in many pieces you will be; it is great fires will be lighted by Finn in Luigne.’

And as it said that, Finn came in, and he made an end of Coirpre, and of his men.”

Here we find another talking oracular head, like that of Bran, which continues to exist after death. What strikes me as most interesting about this tale is that only druids and those of great power were able to make the Ogham markings and read the messages or warnings left on them. Yet Lomna is clearly labelled a fool. The mystic fool, however, is a theme that is universal. One only has to look as far as the Tarot to discover the truth of this statement.

At no point does Lomna “play” the fool in this story. Finn on the other hand not only seems to have a hard time choosing faithful wives, he also needs to use divination to determine how a corpse with its head severed off and missing was killed. Perhaps it is Finn who is playing the fool?

There is more to this story than initially meets the eye.

The Foliage:

The following magical suggestions regarding the use of Alder in ritual are found in Jacqueline Memroy Paterson’s Tree Wisdom: the Definitive Guidebook:

“The appearance of Alder’s purple buds in earliest spring show that the tree is powerful from Imbolc to the Spring Equinox. At this time, as the strength of the sun is visibly growing, meditation with Alder places our feet firmly upon the earth, where we can discern the coming season of light and make wise preparation…

“Because of its associations with water Alder is also powerful in the west of the year, particularly from the Autumn Equinox to Samhain. Then it can be used along with other divinatory herbs in incense and decorations. Specific divination with Alder at this time, especially when looking forward to the new Celtic year which begins after Samhain, pronounces its oracular ‘sacred head’ qualities, allowing us contact with the singing head of Bran to obtain divine specifics for the coming season of darkness. Thus the Alder provides far sight throughout the year.”

Alder can also be used as a stand-in for any protective herb found within any spell. For those following a warrior’s path, the potential magical expressions offered by this “Battle Witch” are intriguing, to say the least.

Our ancestor Celts were passionate people.

“Though looking to the future and not folklore as such, it is worth mentioning that Alder is interacting with humanity in another way by helping us in today’s climate of environmental destruction and restoration. The nitrogen-fixing nodules on the alder’s roots improve soil fertility and so make this tree ideal for reclaiming degraded soils and industrial wastelands such as slag heaps.” Paul Kendall (Trees for Life: Mythology and Folklore of Alder)[xii]

[ii] For a discussion on the Celtic warrior and how he or she relates to contemporary society see the previous post on Alder: https://livinglibraryblog.com/?p=42

[v] Ibid.

[vi] http://www.ancienttexts.org/library/celtic/ctexts/t08.html

see the notes at the end of the document found here.

[vii] Ellison.

[viii] Collins pocket Guide: Trees of Britain and Northern Europe.

[ix] Taliesin is present and survives.

[x] Oxford Dictionary of Celtic Mythology and the Ultimate Encyclopedia of Mythology.

[xi] This was likely a bastardization of the introduced religion of the settled Norse invaders to Ireland (Dublin) and the subsequent exchange and intermarrying of cultures that followed. In the Poetic Edda the first man and woman are Ask and Embla (Ash and Elm).