“The Irish Druids made their wands of divination from the yew-tree; and, like the ancient priests of Egypt, Greece, and Rome, are believed to have controlled spirits, fairies, daemons, elementals, and ghosts while making such divinations.” – W.B. Evans-Wentz (The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries, 1911)

The Roots:

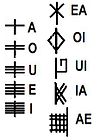

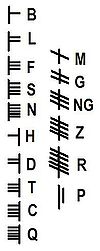

The 20th letter of the Tree Ogham is Ioho, the Yew tree.

The Yew is the tree most often found in mythology to be the Tree of Life or the World Tree[i].

Nigel Pennick in Magical Alphabets calls the Yew the “Tree of Eternal Life.” He also claims that the tree is sacred to divinities of death and regeneration.

Eryn Rowan Laurie in Ogam:Weaving Word Wisdom says that Ioho is the few of longevity, reincarnation, the ancestors, history and tradition. Laurie also says that the Yew is the tree of immortality.

Liz and Colin Murray, in the Celtic Tree Oracle, state that Ioho represents great age, rebirth, and reincarnation. Robert Graves within the White Goddess calls the Yew “the Death Tree.”

John Michael Greer says that the Yew represents “enduring realities and legacies”. He also says that the tree represents that which abides unchanged and the lessons of experience.

The Yew is found in many myths involving tragic lovers such as Deidre and Naisi or Iseult and Tristian. In the legend of the Wooing of Etain Yew is connected directly to the Ogham and to divination. Ioho is also related to tales of hollow trees, the Irish goddess of death Danba, Thomas the Rymer, Cuchulainn and the fairy maiden Fand, and the hidden resting place of Owan Lawgoch. The Yew is also related to the swan through the shapeshifting story of Ibormeith (Yewberry) found in the tale the Dream of Oenghus, and to Oenghus himself who tries to win her love. The age of the Yew is also used as a reference when it is compared to the age of the Cailleach in an old Irish proverb. There are many tribes, names and places named after the Yew throughout the Celtic world. In present day the Yew is still strongly associated to graveyards and, through association, to the Christian Church.

Ioho, the Yew, represents old age, the ancestors, divination, death and reincarnation or rebirth.

The Trunk:

Yew is one of the most important trees found in Celtic mythology.

The Yew tree is often associated with death, dying and the dead. There is an old Breton legend that says that the roots of the Yew tree grow into the open mouth of each corpse[ii]. Yew branches were also often buried with the dead[iii]. Jacqueline Memory Paterson, in Tree Wisdom: the Definitive Guidebook, links the Irish goddess of death Banbha to the Yew tree[iv]. According to Paterson, the Yew was sacred to the goddess and became known as ‘the renown of Banbha’.

The Yew tree is also associated with the fairies and to the Otherworld. As a Yew tree becomes very old its insides melt away making it stronger. It is the “hollow tree” that appears in fairy tales and folklore.

Owan Lawgoch, who we spoke of within the Ivy blog, is a sleeping warrior-king like Arthur. Owan is supposed to awaken and return to rule someday. In Fairy Legends of the South of Ireland, 1825, Thomas Crofton Crocker shares a story regarding Owan Lawgoch’s resting place. Apparently there is a hill on that very spot with a lone Yew tree that stands upon it. When a person approaches the hill, the Yew tree vanishes and will only reappear as the person withdraws once more.

Thomas the Rymer was a Scottish prophet who received his gifts by being the lover of a Fairy Queen[v]. Thomas, like Owan Lawgoch, also waits to be reborn. Folklore marks the location of his second coming as a Scottish Yew grove[vi].

In the Irish myth the Tale of Oenghus the beautiful Ibormeith(Yewberry) transforms into a swan every second year during Samhain. Oenghus in order to win her love becomes a swan as well and they are able to fly off together back to his home[vii].

Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas Rolleston written in 1911 has some interesting mythical details regarding the Yew. The first account is of the great hero Cuchulainn, who we discussed briefly within last weeks blog. When Cuchulainn would meet with his fairy maiden, Fand, it was beneath a Yew tree.

Another story, which is also told by Jacqueline Memory Paterson and Robert Graves, is of the tragic lovers Naisie and Deidre. Naisie was betrayed and murdered in an act of broken hospitality. His wife, the beautiful Deidre, was then shared as a concubine-like prize between two of the killers. Deidre, in her shame, finally threw herself headfirst from a chariot and was instantly killed. In that way the men could no longer have her. The two lovers were then (miraculously) buried near one another within a common ground. Some stories say that they were in the same graveyard, while other stories claim that a church divided them. Either way, Yew trees sprang forth from each of their graves. Their tops then met above the ground where, “none could part them.”

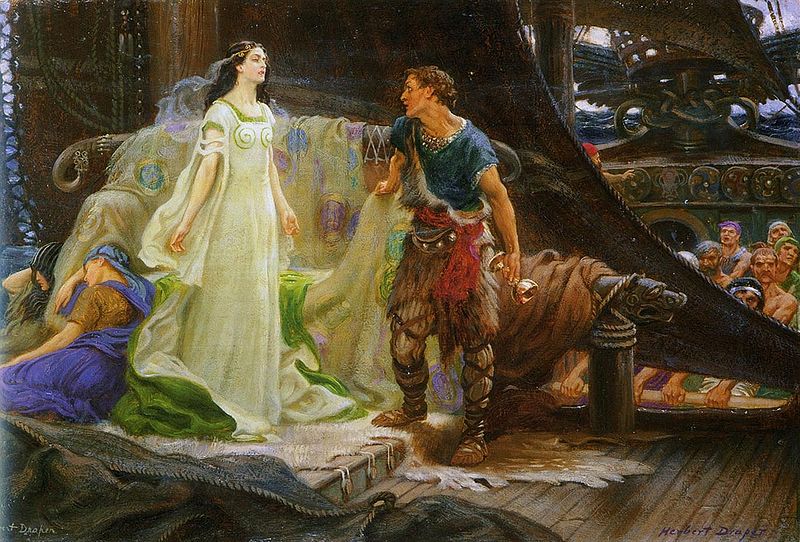

There is a similar tragic love story involving the Yew. The following version of the story is found in Jacqueline Memory Paterson’s Tree Wisdom: the Definitive Guidebook.

(Tristan and Isolde by Herbert James Draper, 1901)

“Cornish legend tells of Mark, a king of Cornwall who was wedded to Iseult, a lady of Ireland who did not actually love him. After their wedding, as they sailed from Ireland back to Cornwall, unbeknown to anyone Iseult’s mother prepared a draught of wine for the wedded pair, in the hopes that a spell would make her daughter fall madly in love with her husband. Unfortunately the wine was drunk by Iseult and Mark’s nephew Tristain, and the two fell passionately in love with one another. The love spell lasted some three years, during which the lovers took many chances to sleep together. Many times they were discovered and reported to the king, whose love for them both pulled him apart. Likewise his kingdom slowly fell apart because of the situation and the gossip it aroused.

“After many partings and tricks of fate the lovers died in each other’s arms. Mark gave them a ceremonial funeral, for he had truly loved them both… within a year yew trees had sprouted out of each grave. The king had the trees cut down but they grew again. Three times they grew and three times he cut them down. Eventually, moved by the love he had felt for both his wife and his nephew, Mark gave in and allowed the trees to grow unmolested. At their full height the yews reached their branches towards each other across the nave and intertwined so intensely they could nevermore be parted.[viii]”

The most interesting story concerning the Yew tree is found in the tale the Wooing of Etain.

Eochy is tricked by a fairy prince, or king, named Midir after he lost a board game to him. Midir, who could choose any gift, requested a kiss from Eochy’s wife Etain. Eochy was forced by his honour to grant the request. Midir then left saying that he will return for the prize. Eochy decided against this and tried to protect his wife but she was spirited away.

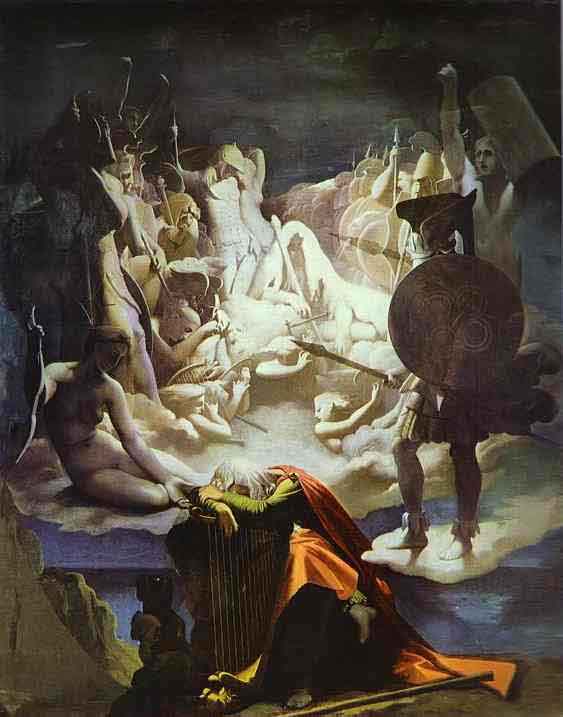

Eochy did not find his wife, even after exhaustive searches throughout the countryside. He eventually consulted the druids as he was desperate to know her whereabouts. A druid cut three yew staves, or in some stories four[ix], and wrote some Ogham letters upon them. These were then cast upon the ground. Through divination the exact fairy mound where Etain was being hidden was determined. After nine years of digging and fighting, Etain was rescued back from the land of the fairies. It is said that this was the war that finally diminished the fairies into a weakened race.

The Celtic myths are ripe with symbolism. For the astute observer the stories hold deeper meanings. They speak to us of relationships with the gods, the seasons, to the earth and ultimately to each other. These stories teach us about living and about dying. Perhaps they teach us of being reborn as well.

In the age of legend there were beings of great power and might. These are found in all of the surviving legends of the Celts. From the 1700s through to modern day we find the newer diminished spirits and fairies. These beings had been reduced in size and were no longer taken seriously in many of the tales. They had lost both their great power and their unsurpassed beauty.

The two theories often put forth by folklorists as to the explanation for what fairies were both pertain to other types of entities. The first explanation is that of diminished gods and the second is that of the spirits of the dead. In either case, a diminishing of size and power is more than slightly symbolic.

All that diminishes and dies will return eventually, in one form or another.

This is the story of the Yew.

The Foliage:

This week I watched starlings gorge themselves on yew berries in a local park.

It is one of my favourite places. The Pacific Yew has its branches entangled with those of a Holly tree. On one side of the pair, nearest the Holly, is an old Oak tree with a spiralling trunk. On the other side, nearest the Yew, is a sickly looking Hawthorn that also has a spiralling trunk.

The starlings would leap from branch to branch, excitedly, while filling their bodies with the ripe fruit. The birds would then quickly disappear into the protective foliage of the Holly if they were startled.

The Yew relies on birds to carry its seed to the hopeful birthplaces of patiently growing saplings not yet realized. This is unusual for needle trees, which usually rely on other means for seed dispersal. The red fruit and lack of sap of the Yew, however, make the Yew an evergreen that is not a true conifer.

Besides being one of the oldest of trees, the Yew is also incredibly poisonous except for the fruit. The seed within the berry and all other parts of the tree are poisonous. The starlings and other birds seem to be able to tolerate the seed. Maybe the seed doesn’t get a chance to break apart completely enough inside of them to pose any real threat?

Colin Murray passed away in August of 1986 just days before his 44th birthday. The Celtic Tree Oracle was published by his wife Liz after his departure in 1988. The means of his death are found in Asphodel Long’s memorial article.

“[Colin] held a strong belief in reincarnation. We know that his death was caused by his eating leaves from a yew tree. In his Tree Alphabet he gives the following definition for Yew: ‘The ability to be reborn, continuously and everlastingly, the reference point for what has been and what is to come.’”[x]

The Celtic Tree Oracle brought with it a means of divination that is the mother and the father of all Ogham divination systems that came afterwards. Like the work of Robert Graves, there are many statements found within the book that do not bear scrutiny very well. We must remember, however, that without either of these pioneers’ research there would be no Ogham divination systems today.

It is appropriate then, that as we discuss the lore of the Yew -from rebirth to tragedy- that we reflect upon the myths that are both modern and mundane. I can contemplate and reflect upon the eating habits of the Starlings to try to have a deeper understanding of the meanings of the tree, but I must go deeper yet.

The Yew is a very toxic plant that is fatal if ingested. The tree presents a fruit, however, that is non-toxic, nutritious, and even has healing properties. Within the core of that fruit is a seed of life. That seed is toxic if it is digested. If it is allowed to pass through the body unharmed it may grow into another Yew tree which would also in turn be toxic and fatal if ingested. Eventually that tree would grow fruit and the cycle would begin once more. The symbolic metaphor may be seen as death in life and life in death.

Colin Murray eloquently said, “Youth in age and age in youth.”

The Yew tree is the Celtic Yin-Yang. In death there is rebirth and in birth there is death.

Many pagan new age systems of divination do not deal with death anymore. It is washed down. Even the death card of the tarot no longer seems to mean death; it means rebirth or even change. I have seen card readers not even use the word death but state that the card means “rebirth.” This avoidance of the word “death” seems to me to be yet another example of how our culture and society views our separateness from nature and ultimately to the whole world around us. Without an appreciation of death there will never be an understanding of life.

The Aspen may be seen as the tree of death and finality within an Ogham divination system. The Yew, the final original letter of the Ogham, is the tree of rebirth. The Yew does not simply mean change.

The Yew represents the rebirth that follows death. This is an important distinction.

“Three great ages; the age of the yew tree, the age of the eagle, and the age of the Cailleach Bearra.” – Irish Proverb (Visions of the Cailleach)

[i] A most common misconception is that the Norse world tree is an Ash but this was a translation error from the Eddas. Yggdrasil is described through translation as either “winter green needle ash” as being poetic or as “winter green needle sharp” as being more literal. I touch on this as well in my Nuin (Ash) post. The Nordic World Tree is generally believed to have been a Yew by those who are aware of this original error.

[ii] Liz and Colin Murray. The Celtic Tree Oracle.

[iv] Part of the triple goddesses that includes Eriu and Fodla found in the Book of Invasions. A mythical explanation for the three names of Ireland.

[v] Quert (Apple) blog.

[vi] Jacqueline Memory Paterson. Tree Wisdom: The Definitive Guidebook.

[vii] Philip and Stephanie Carr-Gomm. The Druid Animal Oracle.

[viii] This story is usually seen to have its roots in Celtic myth. The names of the characters appear in the Mabinogion. Historians sometimes disagree, however, whether this is a Celtic myth or not. The tale is also considered a prototype of the Arthur-Guinevere-Lancelot story.

[ix] Thomas Rollerston, for example, says that there are three staves while Caitlin Mathews in the Celtic Tradition says that there are four.