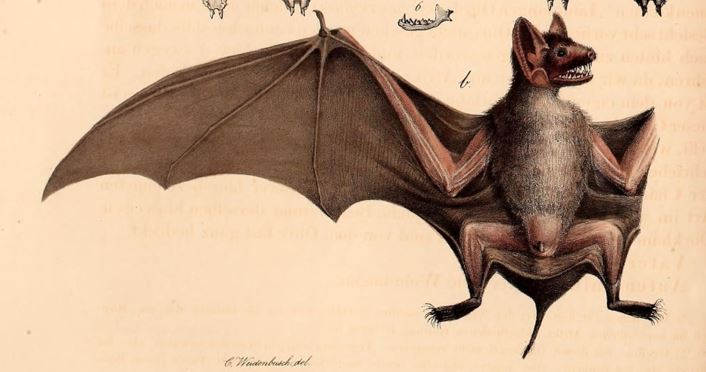

In the land of the Celts – from lonely moors to haunted castles –the bat has long been associated with witches, ghosts, and other tragic beings of the night…

In the 1949 Encyclopedia of Superstitions by Edwin and Mona Radford we find one such example: In Scotland, it was said that when a bat rose quickly from the ground and then descended again, that “the witches hour had come.” This witches hour was, of course, “the hour in which [the witches] have power over every human being under the sun who are not specially shielded from their influence.”

The bat in Celtic folklore wasn’t always bad, though. In A. W. Moore’s 1891 book Folk-lore of the Isle of Man we’re told, “fine weather is certain when bats fly about at sunset.” Likewise, Fredrick Thomas Elworthy reported in his 1895 book the Evil Eye that, “in Shropshire it is unlucky to kill a bat.” George Henderon, in the 1911 book Survivals in Belief Among the Celts, also said “the bat was regarded with awe in the midlands.”

“A bat came flying round and round us, flapping its wings heavily.” – the Bard Iolo Morganwg (1747 – 1826)

Sometimes, the bat could be a fairy (ghost or other discarnate spirit) in disguise. In Thomas Crofton Croker’s 1825 book Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland we’re given one such example: The Phooka – who sometimes took the form of a bat – was basically a trickster-being who hijacked people’s bodies and took them out for a joy ride… a trick modern people might call possession. The story implies that it’s the soul being taken on the journey and not the physical body itself.

“The Phooka would take his victim on great adventures as far away as the moon, [he] compels the man of whom it has got possession, and who is incapable of making any resistance, to go through various adventures in a short time. It hurries with him over precipices, carries him up into the moon, and down to the bottom of the sea.”

Other mythical beings are also associated with the bat. In 1886, Charles Gould in Mythical Monsters identified the Celtic dragon’s wings as those of a bat as opposed to those of a bird. In the 1900 book Celtic Folklore: Welsh and Manx, by John Rhys, we also learn of the Cyhiraeth. “This spectral female used to be oftener heard than seen,” said Rhys. She was usually believed to be a death-messenger, similar to the Banshee, but one who was more likely to be heard than seen. If the title or name of a person could not be heard and understood clearly, then it was assumed that the hearer of the Cyhiraeth’s message would die themselves. Sometimes, instead of words, she would flap her wings against a window at night as a warning that death was coming. The source Rhys quoted in the book said that these wings were leathery and bat-like.

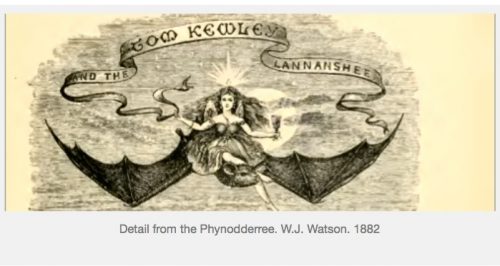

The greatest surviving tale of the bat, however, is the story of the shape-shifting enchantress Tehi Tegi found in A. W. Moore’s 1891 Folk-lore of the Isle of Man:

“A famous enchantress, sojourning in this Island, had by her diabolical arts made herself appear so lovely in the eyes of men that she ensnared the hearts of as many as beheld her… When she had thus allured the male part of the Island, she pretended one day to go a progress through the provinces, and being attended by all her adorers on foot, while she rode on a milk-white palfrey, in a kind of triumph at the head of them.

She led them into a deep river, which by her art she made seem passable, and when they were all come a good way in it, she caused a sudden wind to rise, which, driving the waters in such abundance to one place, swallowed up the poor lovers, to the number of six hundred, in their tumultuous waves. After which, the sorceress was seen by some persons, who stood on the shore, to convert herself into a bat, and fly through the air till she was out of sight, as did her palfrey into a sea hog or porpoise, and instantly plunged itself to the bottom of the stream.”

In this way, the enchantress Tehi Tegi was able to capture the hearts of men through her otherworldly beauty, before dissolving into the shadows in the form of a bat. This, of course, was only after she’d sacrificed the 600 worshippers she had come for in the first place.

In modern times, the bat has become emblematic of Halloween. Halloween, as we know, is the descendent of the Celtic holiday Samhain. In this way, the bat has now become an object of festive tradition instead of a creature loathed or feared.

The bat in Celtic folklore hasn’t lost all of its dark powers completely, however. In Ireland, it’s still said that, “bats commonly become entangled in women’s hair… if a bat escapes carrying a strand of hair, then the woman is destined for eternal damnation[i].” Some people also believe that a bat entering into the home is a sure sign that death will soon follow[ii].

If you’re a lowly man, you could be in trouble if this particular bat portends the arrival of the mighty Tehi Tegi. In this case, the Bat in Celtic folklore might signify a dark destruction for you, as well.

[i] http://www.rte.ie/radio/mooneygoeswild/factsheets/mammals/index2.html

[ii] http://www.batcon.org/index.php/media-and-info/bats-archives.html?task=viewArticle&magArticleID=573

Top image commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Taphozous_nudiventris.jpg