According to lore, the spider in Celtic myth was a beneficial being. It appeared in the old texts suddenly, emerging from some now-forgotten lost older oral tradition, creepy-crawling onto the pages of recorded folklore from out of nowhere.

One of the earliest mentions of the spider can be found in Waltor Gregor’s 1881 book, Notes on the Folklore of the Northeast of Scotland. Here, we discover the spider was once a well-respected creature:

“Spiders were regarded with a feeling of kindliness, and one was usually very loath to kill them. Their webs, very often called ‘moose wobs,’ were a great specific to stop bleeding.”

The author adds the following statements for good measure:

“A spider running over any part of the body-clothes indicated a piece of new dress corresponding to the piece over which the spider was making its way.”

“A small spider makes its nest—a white downy substance—on the stalks of standing corn. According to the height of the nest from the ground was to be the depth of snow during winter.”

Lady Wilde later echoed these sentiments – those of a beneficial spider – in her 1887 book Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms, and Superstitions of Ireland. She claimed the Transylvanians and the Irish shared the belief that one should, “Never kill a spider.” The text implies this would attract misfortune.

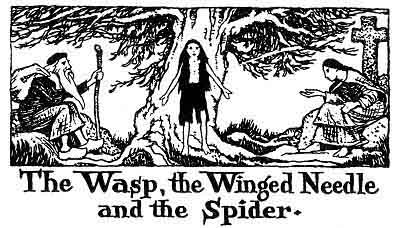

Although Celtic stories involving the spider are difficult to find, they do exist. One tale, involving the Spider, for example, occurs in Elsie Masson’s 1929 Folk Tales of Brittany:

Two brothers are travelling through a forested countryside, when they come across a beggarly old woman. The first brother ignores the woman, while the second gives her all of his coins. As a reward, the old lady gives the generous brother a walnut, which she claims contains a wasp with a diamond stinger.

The older brother becomes annoyed at his younger brother’s generosity, but opts to continue the journey without much further discussion. As they’re riding, however, the brothers come across a young boy who’s shivering in the wind. The younger brother gives the boy his cloak without any thought, much to the dismay of his older brother. The child in return gives him a dragonfly (winged needle), which is being held in a cage made from Reeds. The child claims that the dragonfly was captured from within a hollow tree[i].

The brothers continue on their way, until eventually, they come upon an old man who says that he cannot walk. Filled with compassion, the younger brother gives the old man his horse. In return, the old man gives the generous brother a hollow acorn (Oak nut), which he claims contains a spider.

By this point, however, the older brother is furious. Angry at his younger brother’s foolishness, the older brother leaves him cold, penniless, and without a mount. He tells the younger brother that he will not share his horse, his coin, or his cloak, nor will he wait for him any longer. The older brother seems quite convinced that the younger brother will learn his lesson if he’s forced to walk and to suffer, so he leaves him. As the older brother rides away, however, a giant eagle snatches him from the saddle and carries him into the clouds. The younger brother, horrified, witnesses the act and sees that two eagles have committed it. One of these eagles is white, and the other one is red.

The younger brother, distressed, wonders aloud as to how he will be able to rescue his older brother. Seemingly, from out of nowhere, he hears three tiny voices from out of his pocket. These voices beg to help him. Seeing a possible answer to his dilemma, the younger brother unleashes the three deadly insects. The spider springs forth and immediately weaves a ladder towards the heavens from upon the dragonfly’s back. The group then ascends into the sky, and into the lair of the giant responsible for the kidnapping.

A battle of epic proportions ensues. The wasp stings out the eyes of both eagles and the giant. The spider then attacks, and wraps, the giant within its steel–like web. Suddenly, the eagles switch sides, blindly pecking the giant to death through the spider’s binding webs. The eagles both die on the spot, however, because as the story goes, a magician’s flesh is incredibly poisonous.

(Tom Thumb Spider. Jemina Blackburn. 1855)

In the aftermath of carnage, the dragonfly and wasp transform into horses and attach themselves to the Reed cage, which has now become a coach. The spider, on the other hand, has become the carriage’s groom. The brothers get in, and the coach carries them through the sky[ii]. The carriage then carries the brothers to their horses, where the younger brother also finds a much fuller coin purse and a diamond-studded cloak. Upon arrival, the carriage disappears and the three insects, which have already been transformed once, now assume their true forms. In their place are three shining angels which light up the sky. The brothers fall to their knees and thank the divine beings for all of their aid and for saving their lives.

This tale, though Christian by the time of its recording, echoes a much older belief that all of nature, however humble it may appear on the surface, could in fact be a sacred spirit or divine being in disguise.

The Spider was said to have its own powers though. Sometimes that power was beneficial, and sometimes it brought nothing harm. For example, in the 1899 Prophecies of Brahan Seer by Alexander MacKenzie we learn that:

“A spider put into a goose-quill, well sealed, and put around a child’s neck, will cure it of the thrush[iii].”

Somewhat contrarily, Alexander Carmicheal’s 1900 Carmina Gadelica says there’s a “bloody flux” in cattle believed to be caused by the animal swallowing a water insect or a Spider, believed to have caused the bleeding in the animal.

Understandably, the Spider also has ties to the loom or spinning wheel; which in turn suggests a much older goddess connection. In John Rhys 1900 Celtic Folklore: Welsh and Manx we find the following quote (where the author’s discussing the differences between the Welsh and Breton languages):

“Cor and corryn are also used for the spider, as in gwe’r cor or gwe’r corryn, ‘a spider’s web,’ the spider being so called on account of its spinning, an occupation in which the fairies are represented likewise frequently engaged; not to mention that gossamer (gwawn) is also some-times regarded as a product of the fairy loom.”

Within the Carmina Gadelica we find a more specific connection:

“’Bean chaol a chota uaine’s na gruaige buidhe,’ the slender woman of the green kirtle and the yellow hair, is wise of head and deft of hand. She can convert the white water of the rill into rich red wine, and the threads of the spider into a tartan plaid.”

In 1978, J. C. Cooper stated in An Illustrated Encyclopedia of Traditional Symbols that:

“The spindle is an attribute of all mother goddesses, lunar goddesses, and weavers of fate in their terrible aspect.”

While the statement does seem a little broad, this is likely true in regards to the Celts, as well. In Scottish Fairy and Folk Tales by George Douglas, written in 1901, we find the following statement:

“In the old days, when spinning was the constant employment of women, the spinning-wheel had its presiding genius or fairy. Her Border name was Habitrot.”

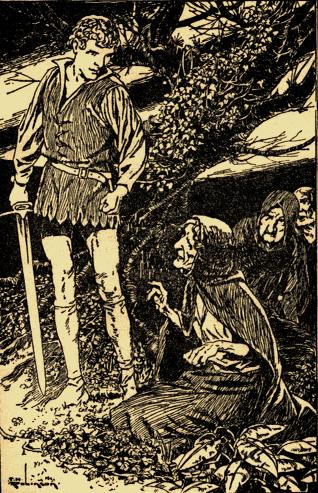

Perhaps, it’s from these two statements that we’re able to surmise an older, and more divine, connection to the Spider. In Thomas Rolleston’s 1911 Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race, for example, we find a story containing similar symbolism to those found in Greek or Norse mythology:

“Finn, it is said, and Conan the Bald, with Finn’s two favourite [sic] hounds, were watching the hunt from the top of the Hill of Keshcorran and listening to the cries of the beaters and the notes of the horn and the baying of the dogs, when, in moving about on the hill, they came upon the mouth of a great cavern, before which sat three hags of evil and revolting aspect. On three crooked sticks of Holly they had twisted left-handwise hanks of yarn, and were spinning with these when Finn and his followers arrived. To view them more closely the warriors drew near, when they found themselves suddenly entangled in strands of the yarn which the hags had spun about the place like the web of a spider, and deadly faintness and trembling came over them, so that they were easily bound fast by the hags and carried into the dark recesses of the cave. Others of the party then arrived looking for Finn. All suffered the same experience— the bewitched yarn, and were bound and carried into the cave, until the whole party were laid in bonds, with the dogs baying and howling outside.”

The hags set about to murder the hapless men, but Goll mac Morna arrived and cleaved two of them in half. The third sister, Irnan, having been initially spared, later returns for vengeance. Goll mac Morna[iv] is finally forced to slay her as well:

“He drew sword for a second battle with this horrible enemy. At last, after a desperate combat, he ran her through her shield and through her heart, so that the blade stuck out at the far side, and she fell dead.”

As a reward, Goll mac Morna is given Finn’s daughter, Keva of the White Skin. The story is incredibly symbolic. If we take the tale as being metaphoric, instead of more literal, then clearly the three hags, and their webs, represent one’s own fate or destiny. While Finn and his men (already semi-divine) are powerless, Goll mac Morna (an exterior force) is able to free them.

The idea of fate, however, was contrary to the teachings of the church. Over time the hags, much like the spider, had become “evil.” The following example from St. John Seymour and Harry Neligan’s 1914 True Irish Ghost Stories illustrates a full negative shift away from the older more favourable viewing of spiders. Long before Marvel created the comic book hero spider man – or even spider woman for that matter – this creepy specter was said to be gracing the walls of one particular Irish manor:

“A strange legend is told of a house in the Boyne valley. It is said that the occupant of the guest chamber was always wakened on the first night of his visit, then, he would see a pale light and the shadow of a skeleton ‘climbing the wall like a huge spider.’ It used to crawl out onto the ceiling, and when it reached the middle would materialize into apparent bones, holding on by its hands and feet; it would break in pieces, and first the skull, and then the other bones, would fall on the floor. One person had the courage to get up and try to seize a bone, but his hand passed through to the carpet though the heap was visible for a few seconds.”

While the tale’s unlikely in a literal sense – at least as far as traditional hauntings go – it does show us that the spider lost its status as a “kindly” being by this point, and instead wore a cloak of blackened “evil.”

At one time, weaving was a necessary practice in the daily life of a Celtic community. As trades became more specialized or industrialized, however, and folk came to view nature as something separate and evil, the spider, the spinning wheel, and the act of weaving itself, lost their mystique, their value, and even their sacredness.

Like it or not, if nature’s ever to be viewed as sacred once more, then so must the Spider. To gaze upon a spider’s web, as it reflects an intricate array of light and complexity, one can be reminded that there’s more to the creeping quiet Spider than initially meets the eye. Sacred or not, the Spider shows itself to be an amazing product of evolution. To the Celtic people of the past, this observation must have been nothing short of divine.

[i] The Hollow Tree is usually a Yew.

[ii] Ancient Alien theorists would claim that this story of flying through the air is indisputable evidence that Aliens co-existed with humans in the past.

[iii] An oral fungal infection.

[iv] Goll mac Morna is described as: “the raging lion, the torch of onset, the great of soul.” He disappears in between the two battles and is not ensnared by the web. The story suggests he’s not human.