(Yew Tree Farm. 1936 postcard[i])

“A yew-tree, the finest of the wood, it is called king without opposition. May that splendid shaft drive on yon crown into their wounds of death.” – Charles Squire (Celtic Myth and Legend. 1905)

1) The Roots: Background information

2) The Trunk: Celtic Mythology and Significance

3) The Foliage: Spells using the Plant

The Roots:

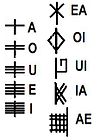

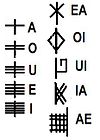

The 20th letter of the Tree-Ogham is Ioho[ii], the Yew tree[iii].

Yew is the tree found most often in mythology as the Tree of Life or the World Tree[iv].

Eryn Rowan Laurie in Ogam: Weaving Word Wisdom said that Ioho (Idad) is the few of longevity, reincarnation, the ancestors, history and tradition. Laurie also said that the Yew is the tree of immortality[v].

Robert Ellison in Ogham: the Secret Language of the Druids said that the Yew represented “death and rebirth.” He also called it “the Ancestor Tree.”

John Mathews interprets the word kennings taken from the Ogham Tract[vi] in his book the Celtic Shaman. There, the phrase “oldest of wood” was given the quality of “wisdom.”

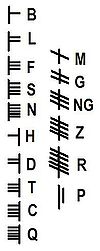

In Celtic Wisdom Sticks Caitlin Mathews said that the Yew “is often found in churchyards, where its association with death and longevity are living symbols of mortality.” She also said that the tree shared the same status as the Oak in Ireland. In her divination system, Caitlin gives the interpretations for the Yew tree as broadening horizons, standing tall, deep memory and observation.

The Trunk:

The Yew is the hollow tree spoken of in folklore and fairytale. In fact, it is one of the most commonly mentioned trees within those Celtic stories.

The Yew tree is often associated with death, dying and the dead. There’s an old Breton legend that said that the roots of the Yew tree grew into the open mouth of each corpse[vii]. Yew branches were also said to have been buried with the dead[viii].

The Aspen may be seen as the tree of death and finality within an Ogham divination system. The Yew, on the other hand, can be seen as the tree of rebirth. The Yew does not simply represent change, however. The Yew represents the rebirth that follows death. This is an important distinction.

Lady Wild spoke of the Yew tree as being “sacred” within the 1887 book Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms, and Superstitions of Ireland. In the 1904 Gods and Fighting Men by Lady Gregory we are told that the Yew was “the most beautiful wood.” In 1877, Lady Charlotte Guest stated in her Mabinogoon notes that the Yew tree was “sacred to archers.”

Alternately, powerful creatures of nature – like the Yew tree – were just as likely to be shunned as embraced. In British Goblins by Wirt Sikes, 1881, we find the following tale:

“Near Tintern Abbey there is a jutting crag overhung by gloomy branches of the Yew, called the Devil’s Pulpit. His eminence used in other and wickeder days to preach atrocious morals, or immorals, to the white-robed Cistercian monks of the abbey, from this rocky pulpit. One day the devil grew bold, and taking his tail under his arm in an easy and degagee manner, hobnobbed familiarly with the monks, and finally proposed, just for a lark, that he should preach them a nice red-hot sermon from the roof-loft of the abbey. To this the monks agreed, and the devil came to church in high glee. But fancy his profane perturbation (I had nearly written holy horror) when the treacherous Cistercians proceeded to shower him with holy water.”

Elsewhere in the same text we are told of couples dancing beneath the graveyard Yew in relatively recent times. These couples would dance beneath the branches on the side of the tree that people were not buried beneath.

Jacqueline Memory Paterson in Tree Wisdom: the Definitive Guidebook said that, “Ghostly faces seen on the trunks of peeling graveside Yews, were thought to be signs of the rising spirits of the dead freed from earthly restraints.”

(Estry Yew in Normandy. Photo by Roi.Dagobert[ix])

The Yew is not just a tree of rebirth, though. It has a direct connection with the Ogham in John Rhys 1900 Celtic Folklore: Welsh and Manx.

“Take for instance the Irish story of a king of Erin called Eochaid Airem, who, with the aid of his magician or druid Dalan, defied the fairies, and dug into the heart of their underground station, until, in fact, he got possession of his queen, who had been carried thither by a fairy chief named Mider. Eochaid, assisted by his druid and the powerful Ogams which the latter wrote on rods of Yew, was too formidable for the fairies, and their wrath was not executed till the time of Eochaid’s unoffending grandson, Conaire Mor, who fell a victim to it, as related in the epic story of Bruden Daderga, so called from the palace where Conaire was slain.”

In some versions of this story there were only three Yew Ogham sticks, or few. In other texts there were four[x].

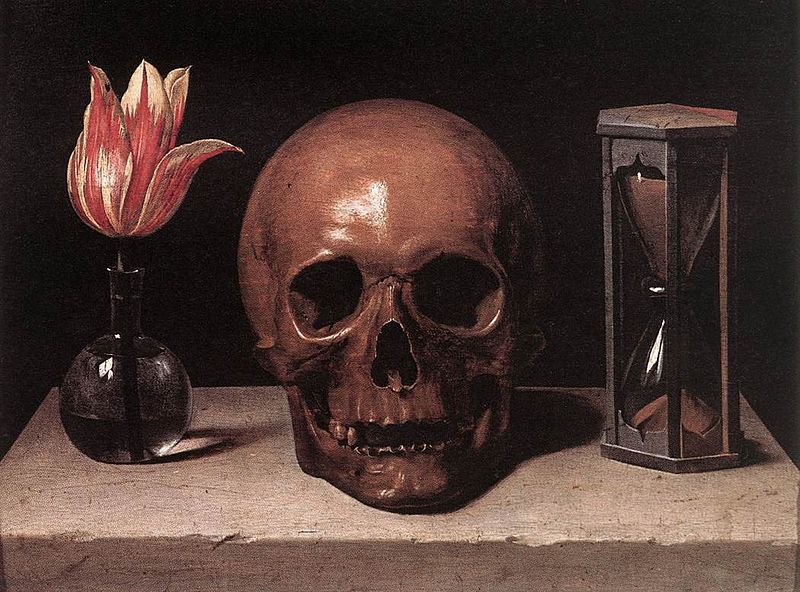

The Yew tree was also often symbolic of romance. In the Irish myth the Tale of Oenghus, the beautiful Ibormeith (Yewberry) transforms into a swan every second year during Samhain. Oenghus, in order to win over her love, becomes a swan as well. The two are then able to fly off together, back to his kingdom[xi].

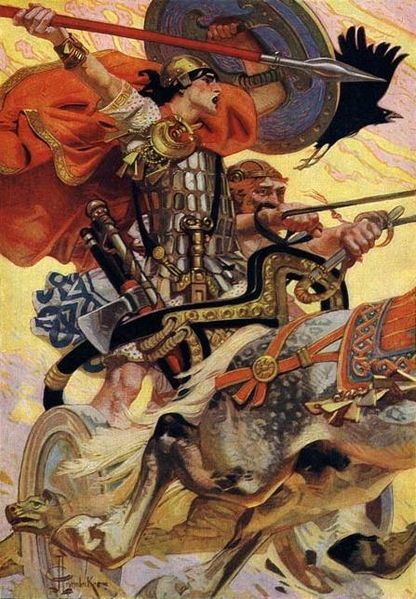

In Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas Rolleston written in 1911 we are told that Cuchulainn would meet with the fairy maiden, Fand, beneath a Yew tree. The lovers meeting beneath a Yew tree in Celtic folklore was a recurring theme. Dead lovers would also often reconnect with one another after death. This was often accomplished by a touching together of branches between these two growing Yew trees.

There are many more examples of the Yew found in folklore. Some of these can be found in the previous Ioho (Yew) post[xii]. This previous post also contained tales of death, fairy abduction, and the story of the passing of “neopagan” father of Ogham, Colin Murray.

The Foliage:

The following spell is found within British Goblins and is used to bring someone back from “fairyland.” The missing person was taken in the early hours of the morning from beneath a magic Yew tree. It was there that he had been sleeping. This particular magic tree was found at the very center of the forest:

“The conjuror gave him this advice: ‘Go to the same place where you and the lad slept. Go there exactly a year after the boy was lost. Let it be on the same day of the year and at the same time of the day; but take care that you do not step inside the fairy ring. Stand on the border of the green circle you saw there, and the boy will come out with many of the goblins to dance. When you see him so near to you that you may take hold of him, snatch him out of the ring as quickly as you can.’ These instructions were obeyed.”

But these sorts of things don’t always work out so well, at least not in this tale:

“Iago appeared, dancing in the ring with the Tylwyth Teg, and was promptly plucked forth. ‘Duw! Duw!’ cried Tom, ‘how wan and pale you look! And don’t you feel hungry too?’ ‘No,’ said the boy, ‘and if I did, have I not here in my wallet the remains of my dinner that I had before I fell asleep?’ But when he looked in his wallet, the food was not there. ‘Well, it must be time to go home,’ he said, with a sigh; for he did not know that a year had passed by. His look was like a skeleton, and as soon as he had tasted food, he mouldered away.”

Maybe his friend should have just left him dancing?

For a more practical use of the Yew, Robert Ellison said that the tree could be used in divination or in spells. The Yew, he said, represented the ancestors, re-birth, death, and could be used “for its powers to cast an arrow a great distance, with strength.”

“And at the same time the poets of Ireland were gathered at the Yew tree at the head of Baile’s strand in Ulster, and they were making up stories there of themselves.” – Lady Gregory (Book of Saints and Wonders. 1906)

[ii] Ioho was the Murray listing. Most Ogham users spell this letter Idad.

[iii] The Ogham is not a tree alphabet, but many use it as such. For more information on the Ogham see previous posts.

[iv] A most common misconception is that the Norse world-tree was an Ash but this was a translation error from the Eddas. Yggdrasil is described, through translation, as either “winter green needle-ash” poetically or as “winter green needle-sharp” as being more literal. I discuss this further in my Nuin (Ash) post. The Nordic World Tree is generally believed to have been a Yew by those who are aware of this original error.

[v] Laurie does not use the Ogham as a “tree alphabet” but shares some tree-meanings in her book for those that do.

[vii] Liz and Colin Murray. The Celtic Tree Oracle.

[x] John Rhys also proposed that these translations that used the Ogham to find the queen might be referring to actual messages sent in Ogham to other druids during the search for the missing bride – as opposed to the magical divination system usually assumed to have been used.

[xi] Philip and Stephanie Carr-Gomm. The Druid Animal Oracle.