The Cat in Celtic lore is a beast both loved and abhorred. Those in pursuit of Otherworldly powers coveted him, but not in a way that lacked cruelty. For those who despised powers said to exist outside of the church, the cat was an indication the devil’s hand was near. This belief would become so prevalent that simply owning a cat would become a dangerous affair when the witch trials began to spread across Europe.

A study of the Celtic cat reveals an ethical dilemma, which will shortly become apparent. A list of sources will be given at the end of this post, but I will not attach them to any one individual statement. By doing this, I hope to provide some accurate broad information while simultaneously avoiding disclosing specific information as far as the ritual use of cats.

It is my belief that spells are symbolic gestures, a prayer embraced by metaphor. Like a New Ager’s ‘vision board’ or the church’s rite of communion. I make these statements not to cause discourse or debate, but to openly criticize anyone who believes that there could ever be a reason to harm an animal for ritualistic purposes. There are those who would obviously disagree with me, but the way I see it, any living being’s life is not worth one’s own personal gain, unless it’s as a source of food. Those who practice these types of rituals are rarely very old, and never very wise. The beings they do seem to attract – metaphorically or not – do not seem interested in the individual’s wellbeing either…

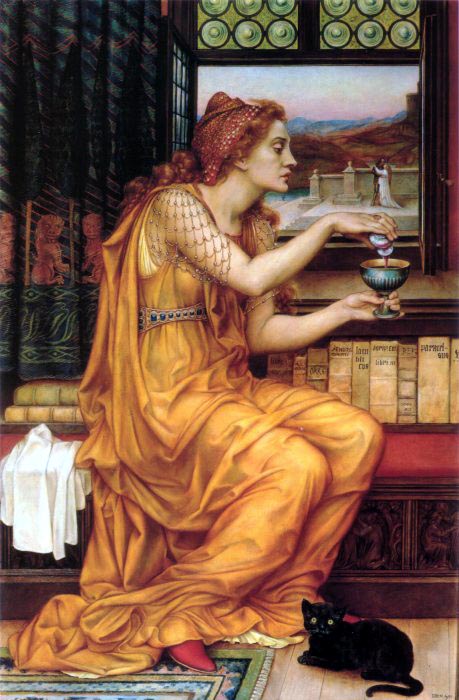

There is a great deal of Celtic lore, which still exists in regards to the cat. Individual body parts were used in a number of spells in several different ways. Additionally, there were love spells that required certain organs ritualistically prepared. There was also a type of divination that involved the slow killing and roasting of a cat in a very specific way. The cat that was used in these spells was usually black. The particular cat most often referred to is also male.

There were spells that used living cats as well. Conducting one spell could transfer a disease from a sick animal to a hapless cat. Several other rituals allowed evil spirits to kill a cat so that the humans would be left alone. On the first Monday of winter, for example, the cat could be thrown outside of the home before the family had exited in order to placate any lingering hungry spirits.

“God save all here except the Cat.” – Irish saying.

There were many opportunities to divine the future by observing a Cat’s actions. If it jumped over a corpse, for instance, the next person who saw it would go blind. If it washed itself rain was coming. If the cat died in the house a human would also die shortly thereafter. If the cat jumped over food being prepared it was said that the person eating it would themselves conceive cats. A cat crossing the path of a bride, or anyone on New Year’s Day was considered unlucky for it warned of negative future events. If the cat crossed the path of a sailor, on the other hand, it was considered to be good luck. If a cat meowed for flesh it was believed that another animal was about to die.

The cat’s life was not highly valued, but the animal itself was treated with a great deal of caution. It was said that a witch’s cat was “endowed with reason.” These felines were also said to be vengeful, so great care was taken so as not to offend them. A cat could also be a spirit, an evil fairy, a shapeshifting witch, a demon, or the devil himself in disguise. For these reasons, the cat was often believed to be a spy for evil beings lurking outside the home. There was also a fairy cat that was known as the King of the Cats. Truthfully, he was much less a king than a vengeful protector spirit of the feline population in general.

There’s also an abundance of lore, which speaks of talking cats. These are often Aesop-like tales or stories of shapeshifting witches. The cats are usually given human characteristics to the extreme. They are bards, warriors, and even sentries. One common Celtic story, for example, is of a Cat who allowed some travelers to feast upon his table. When one of the men tried to take advantage of his hospitality by stealing a necklace, however, the cat became a flaming arrow and incinerated the would-be thief.

In myth, the Celtic cat is a much more ambiguous entity. The Tuatha De Danaan god Nuada had one of his eyes replaced with one of his pet cat’s eyes. Cuchulain and his companions fought three cats in one tale, and in another the Fianna would fight against Cat-headed and dog-headed warriors who were part of an invading land force. Across the water, one of Arthur’s men named Gogyfwlch was said to have had cat eyes. Arthur himself later battled a cat that almost killed him. Elsewhere, there’s the story of an enchanted princess who spent one year as a Cat, one year as a swan, and one year as an otter. This shapeshifting theme, as we’ve seen before, was quite common in the Celtic world.

In the more modern stories, Cats were often associated with ghosts and demons. In one tale, a troublesome cat was drowned with a garter around its neck. The cat would later be seen in a boat with the same garter around its throat. In one early poltergeist account, an apparition of a Cat with a man’s head was seen when a bed was inexplicably set on fire. Though often left out of published accounts of poltergeists, these types of apparitions – that defy logic – are not unheard of. The Bell Witch poltergeist, for example, was said to have first appeared as having had the body of a dog and the head of a rabbit by at least one source. So maybe the apparition was a poltergeist? Then again, maybe the spirit was simply a leftover cousin of the cat-headed people who had fought the Fianna?

The 13th century Irish witch Alice Kytler was accused of having relations with a succubus that sometimes took the form of a black cat. Elsewhere, a source claimed that “the devils” could take the form of a weasel, cat, greyhound, moth, or bird. One Irish witness of witchcraft claimed to have seen a cat-like creature that was three times the size it should have been. The story implies that the apparition was a demon.

In Welsh and French myth, there was also the Palug Cat who was so powerful a being that it was called “one of the three plagues of the Isle of Mona.” It was this cat which Arthur, or sometimes Cai, was said to have defeated in battle. Arthur would later die from wounds sustained in a separate fight, but as many know there are tales that speak of his return to the land. Perhaps, this should offer us some measure of solace, for as one text claims of the cat:

“The wether [goat] they had been fighting with was the World, and the cat was the power that would destroy the world itself, namely, Death.”

No study of the Celtic Cat would be complete, without the mention of phantom cats being reported throughout the United Kingdom today. Despite a lack of evidence of a large black cat ever having been released in England’s rural countryside, there have literally been thousands of sightings in recent years. This cat is usually described as a black panther. It’s the belief of many that these cat sightings can be explained, and there’s a lot of evidence to support this. Until such a time the cat is captured, however, the story remains a modern folkloric account – which just happens to take place on the lands of the ancient Celts.

Although sources seem to disagree with one another in regards to the cat’s nature, there is one level of consistency found throughout. All agree that the Cat harbored, or hid, great power. The Cat in Celtic lore truly was a beast both loved and abhorred, and it would suffer through the ages because of it.

Sources:

Campbell, J. F. Popular Tales of West Highlands. 1890.

Carmichael, Alexander. Carmina Gadelica. 1900.

Crocker, Thomas Croften. Fairy Legends and Traditions. 1825.

Curtin, Jeremiah. Tales of the Fairies and of the Ghost World. 1895.

D’Este, Sorita & Rankine, David. Visions of the Cailleach. 2009.

Douglas, Sir George. Scottish Fairy and Folk Tales. 1773.

Ellison, Emily and Perry, Chuck. Liars and Legends: The Weirdest, Strangest, and Most Interesting Stories from the South. 2005.

Gregor, Walter. Notes on the Folk-Lore of the North East of Scotland. 1881.

Gregory, Lady Augusta. A Book of Saints and Womders. 1906.

Gregory, Lady Augusta. Visions and Beliefs in the West of Ireland. 1920.

Guest, Lady Charlotte. Mabinogion. 1877.

Henderson, George. Survivals in Belief Amongst Celts. 1911.

Jacobs, Joseph. Celtic Fairy Tales. 1892.

Jacobs, Joseph. More Celtic Fairy Tales. 1894.

Kuno, Meyer. The Voyage of Bran. 1895.

MacKillop, James. The Oxford Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. 1998.

Mathews, Rupert. Poltergeists and Other Hauntings. 2009.

Moore, A. W. The Folk-Lore of the Isle of Man. 1891.

Rolleston, Thomas. Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race. 1911.

Seymour, St. John. Irish Witchcraft and Demonology. 1913.

Seymour, St. John & Neligan, Harry. True Irish Ghost Stories. 1914.

Wilde, Francesca. Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms and Superstitions of Ireland. 1887.

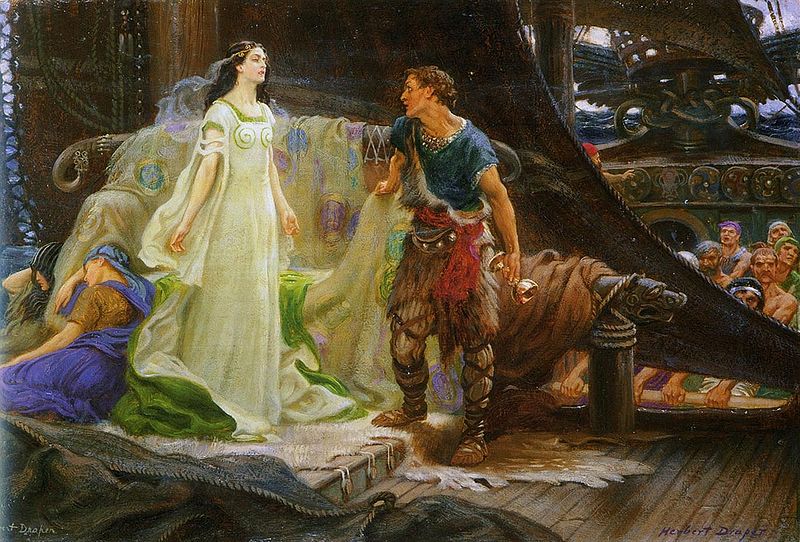

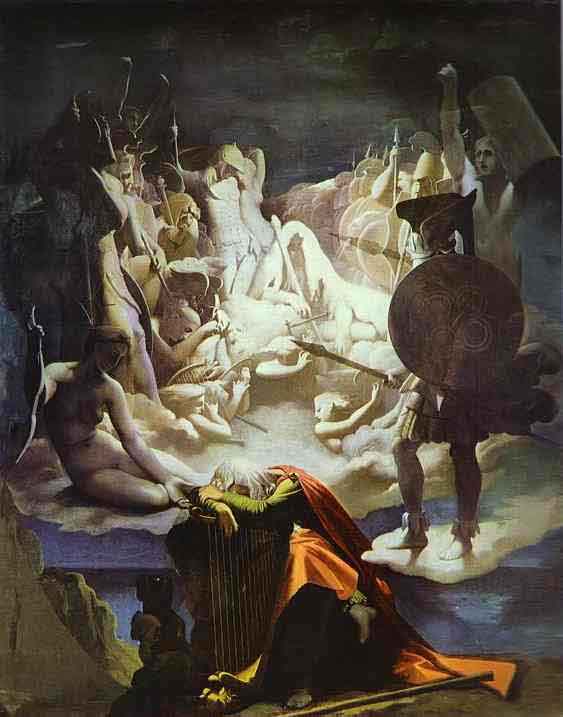

*the top image is by Clement Percheron. It’s available for use through Unsplash.