The Owl in Celtic lore is a creature of shadows and the Otherworld. It’s rarely mentioned in myth, legend, or folklore, but when it is it’s usually spoken of in hushed whispers – accompanied by a warning.

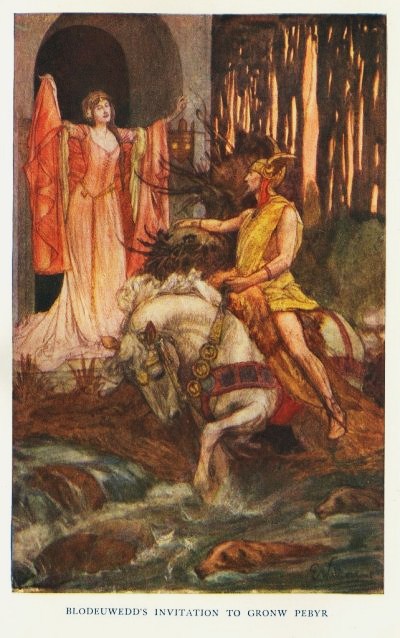

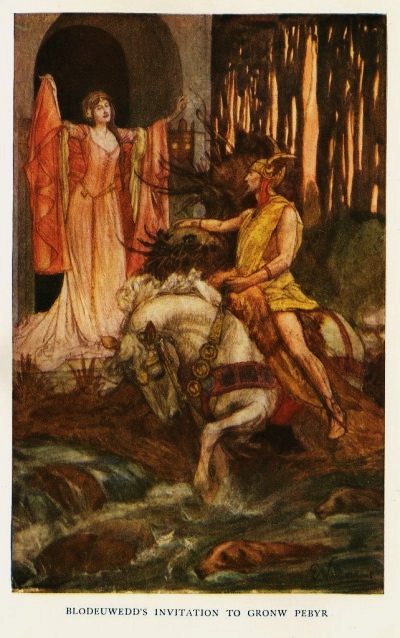

In Lady Charlotte Guest’s 1877 translation of the 12th Century Mabinogion, the Owl’s origins are described in detail. Within the story of Math Son of Mathonwy, the god-like figure Gwydion decides that he must find a bride for his nephew Lleu. The curse upon Lleu, however, is that he cannot ever take on a human wife. To help Lleu out, Math and Gwydion create a woman for him out of flowers. They name her Blodeuedd which is said to mean “Flower Face.” Unfortunately, the new bride betrays Lleu and attempts to have him killed by her new love interest. The assassination attempt fails, however, and the lover is eventually killed. Gwydion then places a curse upon Blodeuedd:

“And they were all drowned except Blodeuwedd herself, and her Gwydion overtook. And he said unto her, ‘I will not slay thee, but I will do unto thee worse than that. For I will turn thee into a bird; and because of the shame thou hast done unto Llew Llaw Gyffes, thou shalt never show thy face in the light of day henceforth; and that through fear of all the other birds. For it shall be their nature to attack thee, and to chase thee from wheresoever they may find thee. And thou shalt not lose thy name, but shalt be always called Blodeuwedd.’ Now Blodeuwedd is an owl in the language of this present time, and for this reason is the owl hateful unto all birds. And even now the owl is called Blodeuwedd.”

In another tale[i], the poet Taliesin asks an Owl about her origins. “She swears by St. David” that she’s the daughter of the Lord of Mona, and that Gwydion son of Don transformed her into an Owl.

There’s a final Owl tale in the Mabinogion–in the story of How Culhwch Won Olwen. While searching for the missing Mabon[ii], some of Arthur’s men are forced to seek out the five oldest living animals and inquire as to his whereabouts. When they eventually do meet the Owl, they discover the bird does not know of the Mabon’s location either. The Owl knows of an animal even older than itself, however, and propels the seekers further along their journey.

In Celtic Symbols, by Saibne Heinz, we’re told of the Sheela na gig, which are “figurative carvings of naked women displaying an exaggerated vulva[iii].” The Sheela na gig are most often 12th-century gargoyle-like sculptures found upon churches. Saibne Heinz claims that[iv], “Some people suspect a resemblance to Owls.”

The Owl is also sometimes believed to represent the Cailleach, the primordial Celtic hag goddess. Philip Carr Gomm, in the Druid Animal Oracle, makes the following statement:

“Because the Owl is sacred to the Goddess in her crone-aspect, one of its many Gaelic names is Cauilleach-oidhche (Crone of the Night). The barn Owl is Cauilleach-oidhche gheal, “white old woman of the night.” The Cailleach is the goddess of death, and the owl’s call was often sensed as an omen that someone would die.”

The Celtic Owl is almost always female. In one Welsh tale, for example (also found in Celtic Symbols), an Eagle searches for a wife. After finally determining that the 700-year-old[v] Owl came from a good family, he hastily marries her.

In Padraic Colum’s King of Ireland’s Son, published in 1916, the Owl is in servitude of evil. The King of Ireland’s Son is led to a cabin by an unusual white Owl. The bird communicates with him by flapping her wings three times. The King of Ireland’s Son soon discovers the Owl is in service of the Enchanter of the Black Back-Lands’ daughter, who just happens to be a shapeshifting swan.

In the notes section of the Mabinogion we’re told the Owl is sometimes seen as the bird of Gwyn ab Nudd, the King of the Faerie. In the 1917 Wonder Tales of Scottish Myth by Donald MacKenzie, we learn of another fairy, a “fairy exile,” called “The Little Old Man” or “The Little Old Man of the Barn.” This wizened looking spirit-being is described as wearing a single white Owl feather in his cap.

In the 1913 Book of Folk-Lore, by Saibne Baring-Gould, we stumble upon a Celtic ghost story, which speaks of the Owl:

“My great-great-grandmother after departing this life was rather a trouble in the place. She appeared principally to drive back depredators on the orchard or the corn-ricks. So seven parsons were summoned to lay her ghost. They met under an oak-tree that still thrives. But one of them was drunk and forgot the proper words, and all they could do was to ban her into the form of a white owl. The owl used to sway like a pendulum in front of Lew House every night till, in an evil hour, my brother shot her. Since then she had not been seen.”

In the 1914 True Irish Ghost Stories by St. John Seymour and Harry Neligan, we find another reference to an Owl spirit:

“A death-warning in the shape of a white Owl follows the Westropp family. The last appeared, it is said, before a death in 1909, but as Mr. T.J. Westropp remarks, it would be more convincing if it appeared at places where the white Owl does not nest and fly out every night.”

The belief that the Owl’s an evil omen is not necessarily tied to just one family, however. In the 1825 Fairy Legends and Traditions of South Ireland, by Thomas Croker, we’re told that seeing “the corpse-bird,” or screech Owl, always foretold of a death. The author compares these sightings to those of the “corpse-lights” which were also said to be seen around the time of death. In the 1881 British Goblins by Wirt Sikes, we’re also told that a Screech Owl’s cry near a sickbed foreshadowed a death:

“This corpse-bird may properly be associated with the superstition regarding the screech-owl, whose cry near a sick bed inevitably portends death.”

Sometimes, the Owl warns of misfortune short of death. In the 1900 Carmina Gadelica by Alexander Carmicheal, for example, it’s said that hearing the “screech” of the Owl meant that the whole year “would not go well.”

Up until the 1950s, Owls were nailed to barn doors as a ward against evil. Strangely enough, it was a common belief that to fight evil one had to sometimes use evil against itself. In this case, the Owl was believed to be a ward against storms, thunder, and lightning[vii].

So it can be summarized that the Owl of the Celts – being a bird associated with twilight – appears white in many of the old texts. It’s is almost always female, as well. The beautiful and Otherworldly Blodeuwedd, for example, was turned into an Owl as punishment for the attempted murder of her husband. Other stories speak of the great age of the Owl, or fear her as a messenger of death. Philip Carr Gomm points out that there’s a direct link between the Cailleach, the Celtic hag goddess, and the Owl, as well.

Could it be a coincidence then, that the only story of the Owl being young and beautiful is the oldest story of them all? Perhaps it is. Then again, perhaps it is not.

[i] As told in the notes section of the Mabinogion.

[ii] The Mabon is described as the divine Celtic youth. The Encyclopedia of Celtic Wisdom. Caitlin and John Mathews.

[iv] Heinz does not reference this claim.

[v] The story actually says she was already old at 700.

[vii] http://www.telegraph.co.uk/earth/3301816/Barn-owl-is-Britains-favourite-farmland-bird.html article provided by @sophiacandle http://divinecommunity.wordpress.com/